Across the street from the Santa Ana Regional Transportation Center sits the four-story Depot at Santiago, a 70-unit mixed-use affordable housing development currently under construction. Also near this construction site is the Logan neighborhood, Santa Ana's longtime refuge for low-income Mexican immigrant communities.

The Depot is the first and only affordable housing development in Orange County being funded with cap-and-trade dollars from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). The site's close proximity to public transit, the area's high pollution burden, and the lack of local affordable housing helped it qualify for $3.9 million from the Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities program.

There are not many cap-and-trade projects like the Depot — with direct, measurable benefits for disadvantaged communities — in California, and this is true as well for Orange County. This is important because the law calls for 25 percent of GGRF dollars to be spent within disadvantaged communities, and an additional 25 percent to be directed toward low-income households. A recent study released by the University of California Irvine's Community Resilience Projects took a deeper look at the local impacts of cap-and-trade-funded projects in Orange County, and concluded that they may provide fewer benefits to vulnerable communities than they claim to.

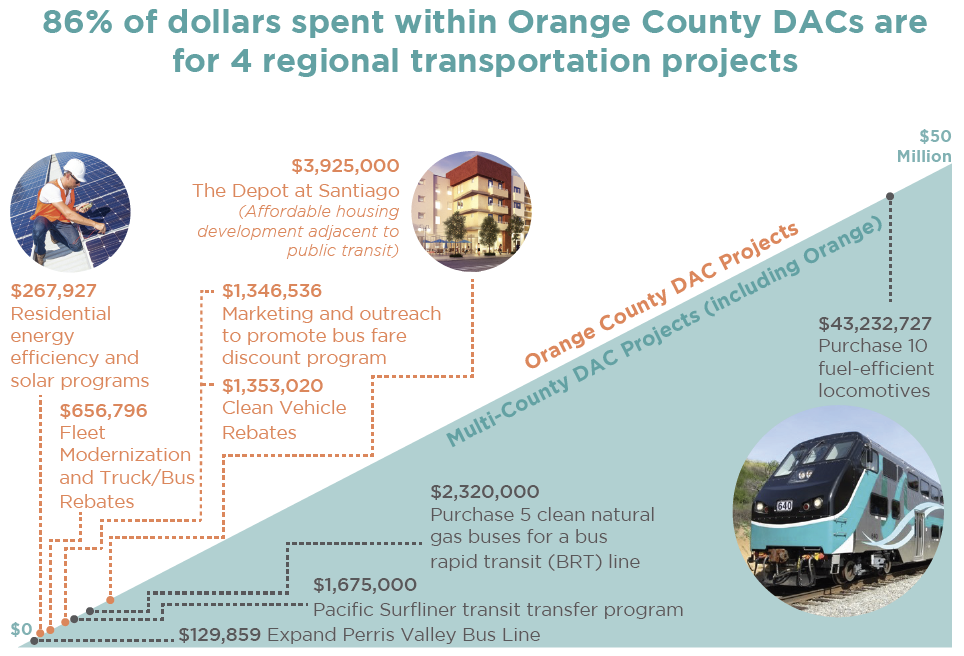

One reason for this could be Orange County's preference for multi-county projects. From 2012 to 2016, Orange County received $88.6 million from the GGRF. Most of that money — 86 percent of it — went to four regional transportation projects. Roughly half, about $43 million, was used to purchase ten fuel-efficient locomotives for Metrolink, and some $2.3 million was used to buy five natural gas buses for OCTA's rapid bus fleet. In addition, $1.6 million went to Amtrak's Pacific Surfliner transit transfer program, and $129,000 was spent on expanding a Perris Valley bus line.

The issue with this, according to the study, is that purchasing buses or investing in transit "is likely to have a more diffuse impact on individual disadvantaged communities because the nature of the investment is not directly place-based." While documents and applications claim that more than $54.9 million in GGRF dollars are being spent to benefit Orange County's disadvantaged communities, the impact — of lower emissions, for example — only occurs while the buses and trains are passing through the area. Other causes of emissions or health and economic burdens, such as high volumes of traffic, proximity to industry, lack of access to transit, or lack of affordable housing near transit hubs, remain unaffected.

The study's authors calculate that, instead, only $7.5 million of the funds should be considered directly benefiting Orange County households and cities.

"We must be careful not to assume that dollars spent on multi-county investments will have the same local impact as dollars that are invested solely in a single disadvantaged community," they write.

Orange County is not alone on this issue. In San Bernardino, roughly ninety percent of all GGRF projects that claim to benefit disadvantaged communities are multi-county projects, while in Riverside the portion is eighty percent. Los Angeles and San Diego are both investing between thirty and fifty percent of their GGRF dollars in multi-county projects.

Neighboring counties that have favored single-county projects in disadvantaged communities were Imperial (90 percent of projects), Los Angeles (56 percent) and San Diego (62 percent).

Potential GGRF projects are ranked according to a number of factors, including a score for the disadvantaged communities they purport to serve. The score comes from CalEnviroScreen, a state tool that aggregates environmental and population data for every census tract to identify communities with the greatest pollution burdens and health vulnerabilities. Los Angeles has the highest number of disadvantaged communities, with a population of 4.3 million living in those areas. That is more than double the number of people living under similar conditions in Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Imperial, and San Diego counties.

The study also points out that a recent update to CalEnviroScreen reduced the number of officially disadvantaged communities in Orange County, from 86 census tracts to 69.