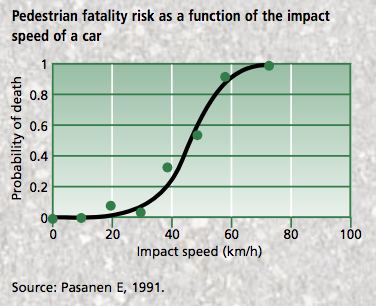

Research consistently shows that speeding vehicles greatly increase safety risks, for people in cars as well as for pedestrians around them. The faster a vehicle goes, the longer it takes to come to a stop. Faster speeds lead to higher likelihood of a crash, and the higher the speed of a crash, the higher the likelihood of serious injuries and fatalities. The chart above, from a World Health Organization report on traffic injury prevention, shows the relationship between speed and risk to pedestrians.

But cities in California have been hamstrung when it comes to lowering speed limits.

State authorities, to prevent local jurisdictions from creating speed traps—where speed limits are abruptly lowered so that local police can charge drivers for speeding and thus make money for a municipality—have severely restricted the way speed limits can be set in California. That has led to some unexpected and negative consequences for safety.

If a town wants to lower a speed limit, for example as part of an effort to make their downtown safer, it must conduct a speed survey of vehicles currently driving on the road. Then, says the law, it must set the speed to match however fast 85 percent of the drivers go. There is no accounting for either design or safety, except for one point: if an engineering survey were to show a need for a lower speed limit than that 85 percent rule would call for, then the results could be rounded downward.

One result of the kind of thinking this rule produces is that engineers have a hard time understanding that designing for slower speeds is a thing—that, for example, narrowing lanes or adding bulbouts could lead to safer outcomes for all road users.

And it has led municipalities to avoid even trying to lower speed limits. If most people are speeding in an area, the results of the required speed survey may force them to raise the speed limit instead. Nevertheless, cities are required to regularly update their speed limits, and must do so if they wish to enforce the limits. Combined with engineers' tendencies to overdesign streets for “safety,” with wide lanes and clear sight-lines, California has witnessed a steady increase in speed limits over time.

This is pretty much the opposite outcome from what safe streets proponents would like to see.

Or course, speed limits, which after all are no more than numbers on signs, are not the complete solution to making streets safer. But they are one important tool, which cities are currently not able to deploy effectively.

That may change, if a bill by Assemblymember Laura Friedman (D-Glendale) is successful.

Glendale, says Friedman, has more than its share of pedestrian crashes and injuries, and the city has been dealing with the problems of street racing as well. Looking around for inspiration, she found L.A.'s Vision Zero efforts that create a framework for reducing casualties. Among its recommendations are to look at the actual crashes on a street or road or network and focus efforts on those areas that have the most serious problems.

Her bill would add only a few words to current law, creating another exception to the 85 percent rule. That is, under A.B. 2363, a local jurisdiction could use information from a collision survey to help it lower a speed limit. So if an area is found to have a high crash rate, an exception can be made.

Her staffers say Friedman is working with a number of organizations, including the city of L.A., the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition, CalBike, California Walks, and the CHP, to come up with a definition or guidance on what such a collision survey would entail.

Rock Miller, an engineer who has been working to change 85 percentile rule for a number of years, says the bill would need further amendments for it to work. For one thing, there is no provision for lowering the speed limit farther than just rounding down from the 85th percentile results.

Miller says that opposition to loosening speed limit requirements has been intense. A time-limited pilot program could get more support, and could be studied for effectiveness as well, he said. He also thinks it worth considering for the legislature just to direct Caltrans or the CAMUTCD, which is currently tasked with writing speed limit rules, to figure it out themselves, as they have said they have no authority to make changes.

At least Assemblymember Friedman has started the conversation. Let's hope it leads to slower speeds and safer streets.