Whether the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza will become the next Glendale Americana remains to be seen, but with the City Planning Commission’s approval of the master plan for the “urban village” July 13, it is clear that major changes are indeed in store for one of California's oldest malls and L.A.'s African American community [listen to the hearing audio here; find plans for the site here].

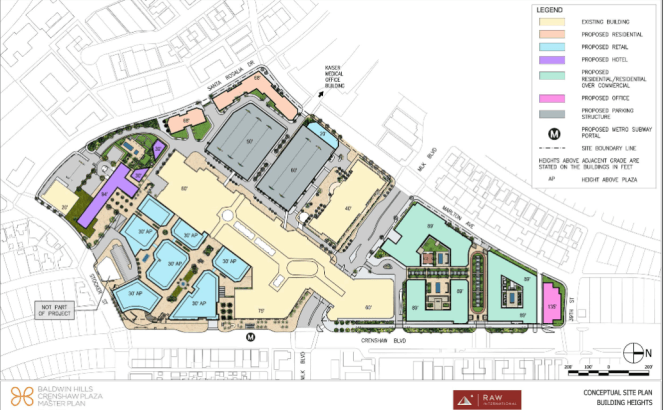

The proposed changes would result in a total of 961 mostly market-rate residential units (551 condominiums available for purchase and 410 apartments for rent), up to 400 hotel rooms, 331,838 square feet of retail/restaurant space, 143,377 square feet of office space, 6,829 parking spaces, and 885 bicycle spaces at the intersection of Crenshaw and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevards. Among the benefits for the community requested by the commission are the requirement that twenty-five percent of both construction and operations hires be local and the setting aside of ten percent of all residential units for affordable housing (five percent for workforce housing and five percent for very low-income residents).

The new complex would be a far cry from the open-air mall first built there in 1947 (below). But it’s not the first major intervention the site has seen, either. Nor is it the first time the city is looking to the mall as having the potential to give the area an economic boost.

Malls-as-Revitalization: an Unhappy History

In the mid-1980s, the mall was transformed into an enclosed space in what would be the first redevelopment project of Los Angeles' Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA). The mall had originally been built in 1947 to serve whites, but the striking down of racially restrictive covenants in 1953 and the loss of the ability to sue other whites for the loss in property value that accompanied the arrival of more affluent black families to the area sent many fleeing. Some more progressive whites in Crenshaw favored integrated neighborhoods that they felt managed to strike a racial "balance" among blacks, whites, and the Japanese, and they worked to retain white residents. But as civil unrest gripped Watts in the 1960s and elsewhere, they, too, would eventually leave the area behind. By the time the City Council earmarked the $100-million makeover to put the mall at the center of efforts to "revitalize" the area in the 1980s, the vast majority of whites were long gone.

It was a heady moment in time for malls, more generally. But the success of malls was largely due to a combination of financial incentives for developers and the fact that they were one-stop commercial and entertainment oases well outside of the urban centers that so many suburban denizens had fled. Their ability to revitalize urban centers - where the financial incentives were far less robust and where a customer base of means had largely disappeared - was much less certain. Since the late 1990s, they have been on the decline everywhere, with up to a quarter of the thousand-plus remaining malls expected to close in the next five years.

The revitalization effort at Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza encountered problems almost immediately when stakeholders, including current planning commissioner and then-president of the Urban League John Mack, pointed out how few African Americans were on the construction crews. The developer had made a verbal promise to then-mayor Tom Bradley that nearly a third of the approximately 1,000 workers on the site would be black. It already wasn't a number that sat well in a community that was 80 percent black at the time, and it didn't appear that the crews even came close to that smaller target. How would these failings bode for the composition of the 120 new businesses the mall was expected to hold? And who would comprise the approximately 3,500-strong workforce once the mall opened?

After the public outcry over the lack of African-American representation on the construction site, developer Alexander Haagen worked to remedy the deficiencies in hiring. Still, stakeholders were right to have been concerned.

When it reopened to much fanfare in 1988, the mall was still struggling to attract tenants, including the kinds of major anchor retailers that would draw the area's more affluent African American residents to the site. Confidence in Haagen's interest in making that happen was further shaken when he fired the black manager of the project and replaced him with a white management team.

Three years after reopening, the mall continued to operate at a loss and had only filled 60 percent of the available retail spaces, prompting Mack to again voice his frustration, this time with the refusal of major upscale retailers to see past harmful stereotypes and invest in black communities.

That frustration seemed only to strengthen the resolve Mack and others had to continue to push for a minority-owned movie theater to step in and act as the anchor business that major retailers were unwilling to be. Something that was far easier said than done, especially at that time.

Across the country, movie theaters had largely disappeared from urban cores as whites fled the cities. That meant that if residents of color wanted to see films, they would have to trek to more affluent areas and suburbs, where they were not always welcome and also very unlikely to see black-centered stories play out on screen.

The Baldwin - South Central's only black-owned theater (and one of the few black-owned theaters in the nation) - had survived thanks, in great part, to the middle-class black community that remained in South L.A. and supported community-serving programming. Unfortunately, it also eventually succumbed, sunk by largely external circumstances. The cost of going up against the deals made between distributors and major movie houses to get first-run films and the challenges of getting a loan to do renovations (e.g. convincing lenders that there was significant demand in a black community) had finally compelled the original owners to sell in 1992. Soon after, accusations of financial misdoings soured the partnership between AMC Theaters and Economic Resources Corp., who had bought the business as part of their "Inner City Cinemas" joint venture to bring multiplexes back to urban cores. The dissolution of the venture sounded the final death knell for the historic theater.

The collapse of that joint venture in 1993, in turn, meant that the deal that had been in the works for years to have Inner City Cinemas build a multiplex at the plaza suddenly evaporated, threatening the likelihood that a minority-owned theater would ever take up residence there.

When former Laker Magic Johnson agreed to launch his own multiplex venture and the Magic Johnson Theater opened at the plaza in 1995, stakeholders wondered if the shopping center might finally be turning a corner. They doubled down on their efforts to attract Macy's, even holding a parade explicitly aimed at convincing the retailer that there was a strong customer base ready to welcome it with open wallets.

Unfortunately, theaters in malls - even black-owned ones - haven't proven particularly magical with regard to larger revitalization objectives. While the theater was an important addition to the community, any boost to mall patronage was hard to quantify. Not only did the theater fail to convert the mall into a destination, some even felt the younger patrons drove the older, more affluent ones away. And the Macy's - the very same Macy's which stakeholders had pushed so hard to attract - closed within just three years of its arrival.

Using Commerce to Boost Community - What Does it Take?

When Capri Capital Partners shelled out $136 million in 2005 for the property, they knew exactly what they were getting: a poorly managed revitalization project that had limped along against a greater backdrop of disenfranchisement, disinvestment, and general disrespect for the black community.

For the mall to transcend both this context and the fact that malls had already been in decline for some time, the new owners decided that, in addition to a significant injection of capital, it needed greater connectivity between itself and the community it was meant to serve.

As such, one of Capri's first moves was to bring on the Debbie Allen Dance Academy as a tenant. Free performances were incorporated into the mall’s efforts to build a stronger relationship with the community, which would later grow to include free fitness classes, concerts, a weekly farmers’ market, the Pan African Film and Arts Festival, and myriad other celebrations.

Smaller upgrades shortly after the mall’s purchase also paved the way for Capri to sink $35 million into the first phase of the modernization of the property beginning in 2011. A partnership with Rave Cinemas would direct eleven million of those dollars into overhauling the Magic Johnson Theater (which had been sold in 2004 and closed in 2010) and construction of a new promenade. The proposed changes helped attract new tenants to the mall (Macy's eventually returned), including a high-profile sit-down restaurant and other retailers and eateries, which allowed it to aim its branding at more discerning customers. Yet Capri also ensured that construction included 30 percent local hires, so as not to leave those in the lower strata behind, and worked with Rave Cinemas to hire locally.

When 900 people showed up for the one-day job fair held to find 80 workers for the movie theater, however, it suggested that the need within the community ran far deeper than what a few jobs might fix.

That great need is also hidden behind the figures aimed at showcasing the potential buying power of the area. There is indeed a “Black Beverly Hills” just up the hill from the mall and a well-to-do community of black homeowners in the beautiful neighborhoods surrounding Crenshaw. With the exception of Ladera Heights (90056), however, the majority of households in the surrounding zip codes earn below $75,000 a year. And they don't just earn below that figure - census data indicates as many as 30 percent of residents in many of the same zip codes listed above live below the poverty line.

As the first fired and last hired when the last recession hit, black unemployment across L.A. County is nearly double that of whites at present, and unemployment rates in some South L.A. neighborhoods match those seen in the lead-up to the 1992 uprising. Area schools tell yet another story: foster youth have comprised as much as 54% of the student body of nearby Crenshaw High School in recent years, while just over half of the caregivers for the larger student body reported being unemployed.

Yet, rents continue to rise and home values have jumped by more than 40 percent in the heavily black communities along the Crenshaw Line as the promise of transit fuels speculation.

A genuine commitment to the larger community, then, means that major projects must contend with balancing not just the needs of the wealthiest against those of the poorest, but also the damage done by decades of disinvestment and disenfranchisement in these communities, and the extent to which it has left them vulnerable to cultural, social, economic, and physical displacement.

It's a topic Quentin Primo III, CEO of the Capri Investment Group - one of largest minority-owned investment firms in the country, has not necessarily shied from broaching publicly. The redevelopment of the mall into an urban village, Primo told the planning commission this past July 13, was also aimed at "disrupting [the] sustained lack of investment that followed" the waves of social upheaval the area has seen since the 1960s.

As such, he and others representing the project contended, a retail center would not be enough on its own, especially in an increasingly digital world.

Instead, the combination of a 400-room hotel with meeting rooms, restaurants, and a banquet facility, a 14-story office tower, nearly 1,000 units of housing (both for rent and for purchase, mostly at market rates), the incorporation of the Debbie Allen Dance Academy into the mall itself, and new dining spots, entertainment options (including a bowling alley and a bar), and promenades where residents and visitors alike could gather and relax right off a major transit line from the airport would help put new jobs in close proximity to those who needed them most while offering amenities that residents have clamored for for years.

The project, in theory, will help bridge some of the gaps a purely commercial project cannot: the potential for job creation is high; infill development means there will be no direct displacement; the added residential density and hotel (the first in the area) could boost community-driven efforts in Leimert Park Village and along Crenshaw to become a hub for black- and diaspora-centered innovation, entrepreneurship, and creativity; higher-end retail and services should make it more appealing for the area's affluent residents to spend their dollars there, making it more sustainable and more likely to attract other investment to the area (malls aimed at middle- and lower-class customers have faltered); and the greater openness and connectivity to Crenshaw Boulevard could have spillover benefits for other businesses along the corridor.

Considering the decades stakeholders have spent trying to convince investors that their community has buying power and is worthy of engagement, it's easy to see why so many were speaking up in favor of the project at the hearing.

But a closer look at how this will all come to pass also makes it easy to see why others expressed serious concerns.

Detractors see Devils in the Details

The proposed development agreement (DA) called for just ten percent of the construction hires to be local. And while a labor agreement with the hotel workers union would ensure the hotel was union-staffed and efforts would be made to invest in job training (including on-site job fairs, the setting aside of an on-site space to conduct trainings, and the allocation of $1.5 million to L.A. Trade Tech's training programs), there was no guarantee that any of the rest of the operations staff for the project would be local hires.

In the past, Primo had explained, his firm had prioritized local hiring even when there was no specific mandate, and this project would be no different.

Commissioner Mack was among those who found that approach unconvincing.

"I think it's important for my colleagues to keep in mind," Mack said as the commissioners opened discussion on the merits and deficits of the DA, "unemployment is disproportionately much higher within the African-American community, and within this community. I think we need to not limit ourselves and not think too small when we talk about local hire...I would throw out increasing it from ten percent to fifty percent, both for construction and for permanent jobs." Construction jobs were short-term fixes, he continued, picking up on a point raised by commissioner Caroline Choe. For this project to genuinely benefit the area over the long term, "a high priority needs to be on local hiring, particularly in this community."

Of even greater concern to many was the fact that the five percent of units to be set aside as affordable housing (a total of about fifty units - twenty-seven for-sale and twenty-three rental) would probably still remain out of reach of the local community.

In explicitly designating those units as "Workforce" housing, the developer would be targeting folks making between 120 and 150 percent of the area median income (AMI) - nearly $100,000 for a family of four.

That pricing was so high, a member of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition (CSC) quipped, it appeared that the developer was looking to reclaim the area for the whites that had once fled it. CSC Executive Director Damien Goodmon, once a supporter of the project, turned to the crowd while making his comments and asked the those present to raise their hands if they earned over $100,000. When few hands went up, even among project supporters, he turned back to the commission to argue that people didn't realize they were essentially pricing themselves out of their own community.

While Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson's office did not go that far while expressing support for the project, they did underscore the importance of affordability and attention to the needs of the existing community. The fact that this kind of project - one of the largest housing projects in the city and a landmark for South L.A. - could finally mark the beginning of the end of "nearly half a century of neglect and disinvestment," capital projects manager Joanne Kim said, did not exempt it from being "done right." To that end, she said, "District 8 shares the concerns of many of the speakers who have already talked about making sure that this housing is affordable to residents who already live in the district and call South L.A. home."

The office recognized the importance of having an African-American developer willing to invest in a community that so many had refused to take a chance on, Kim concluded. But they looked forward to continuing to work with the developer to make sure that the project was attuned to the community's needs.

Detractors of the project insist that's not enough.

With the median income for African Americans across L.A. County being just under $40,600 - approximately $15,000 less than the median income for all of Los Angeles - the combination of market-rate and workforce housing would effectively shut out a significant proportion of potential black homeowners or renters.

That's a tough sell when held up against the significant drop the black community has already seen in population. Citywide, the total black population has dropped by 100,000 since the 1980s and now hovers well below 10 percent. Between 1990 and 2009, the black population of South L.A. itself decreased by 16.4 percent. Since then, the combination of the foreclosure crisis (South L.A. was one of the hardest hit areas), the fact that African Americans were the slowest group to be rehired after the recession, and the weariness with disenfranchisement and increasingly high housing costs that have pushed so many to Lancaster, Palmdale, Victorville, and even out of state have all increased the likelihood that new tenants will not be African American. Moreover, detractors fear, this project - in combination with other major public and private investments in the area - may further fuel the indirect displacement already underway (thanks in great part to the opening of the Expo Line and the expansion of USC).

Moreover, as noted by commissioner Dana Perlman, the project is sited at a future transit station and will be built out over the course of twenty years - at the end of which the city will likely be looking at a very different landscape. Safeguarding only five percent of the units as affordable, and as not particularly affordable at that, just didn't compute.

When asked about how he responded to community demands for much higher percentages of local hire and truly affordable units, Primo pointed the finger elsewhere.

With regard to the five percent affordability, he said, "That reflects the recommendation of the neighborhood council, the Empowerment Congress. That recommendation was made, just to give you a little color, because of the concentration of affordable housing in [the Crenshaw] area...It is disproportionately represented with affordable housing. So the idea was to bring market-rate, middle-income housing to the area to help improve schools and create jobs and do all the things that investments in communities like this do."

He implored the commission to instead grant the firm maximum flexibility and discretion, he said, because it would make it easier to attract the half-million-plus in capital that they needed to raise to complete the project.

Meaning, it seems, that the stigmas around affordable housing and investments in black communities remain wholly intact.

That the developer is still working to navigate those stigmas is likely no surprise to anyone that has visited the Transforming Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza website. The preponderance of the images there are of happy visitors that are not particularly reflective of the existing community. On the Arts & Entertainment page, for example, the blurb describing their commitment to weaving local culture "throughout all the plans" is paired with a distinctly non-African American set of shoppers.

Similarly, the job creation page, despite promising to create thousands of jobs to stimulate the local economy, likely does more to stoke the fears expressed by the council office, the commissioners, and the community than assuage them (below).

Interestingly, rather than defer to the developer's pleas, the planning commissioners instead called upon the development agreement approved for the billion-dollar Reef project for guidance in making their decision.

At the time the Reef project was debated last year, the commissioners had predicted its massive size and scope would make it precedent-setting. And so it appears to be. Highly imperfect as that agreement was - commission president David Ambroz even reminisced about his disappointment at not seeing more affordable housing incorporated into the project - the similar scope of the developments (the Reef will host over a thousand residential units, a hotel, a mobility hub, and major retail and services) suggested there was room for greater concessions on the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza project.

As a result, the commissioners pushed to see a total of ten percent of all housing units (both rental and for-sale) be affordable. Five percent of both for-sale and rental units would remain categorized as Workforce housing and five percent of each would also be set aside at the Very Low-Income level. With regard to hiring for both construction and operations, the commissioners moved to require that twenty-five percent be local, and again referred to the Reef DA to suggest that tiers be used, with the first tier of "local" defined as within the district.

Other aspects the commissioners discussed included directing that the $100,000 intended for mitigation of congestion within a twenty-square-mile radius instead be earmarked for three square miles in the immediate area in order to have a tangible impact. The resulting bikeway, sidewalk, and other improvements should all be aimed at making it easier to walk or bike to and from the site, commissioners suggested, to encourage connectivity, to reduce congestion from locals making short trips, and to encourage use of the mobility hub planned for the site. Commissioner Renee Dake Wilson also asked about ensuring that a percentage of retail space be set aside at reduced rents to allow local businesses to move in; the developer said that they regularly set aside spaces for minority-owned businesses on other projects.

With the project coming before the commissioners as a master plan for a site to be developed over an unclear timeline spanning many years rather than specific plans for specific buildings, there was a limit how much input the commissioners could offer. So while they contemplated asking for even more than twenty-five percent local hire or ten percent affordable housing, in the end, they voted unanimously in favor of the more conservative percentages and moved quickly on to the next project.

Moving Beyond Spot Thinking

If there was one thing that stood out about the three-hour commission hearing it was how little discussion there was about where the project fits into the larger array of changes coming to the community and the potential for indirect displacement and/or a significant shift in character that the confluence of those projects represent.

Earlier this year, Kaiser Permanente broke ground on a $90-million, 100,000-square-foot medical facility designed to encourage healthy living by making two-mile walking path, and outdoor event space accessible to the public at the adjacent Marlton Square site. Less than a mile north on Crenshaw, at Rodeo Road, the mixed-use District Square project will replace the Ralph's/Rite-Aid complex torn down a few years back. There's also the massive residential tower planned for the La Cienega/Jefferson station a mile to the west along the Expo Line, the Rail-to-River bike and pedestrian path project planned along the Slauson corridor (opening in 2019), the NFL stadium under construction in Inglewood (slated for 2020), and, of course, the opening of the Crenshaw Line (slated for 2019). Smaller projects include 78 transit-oriented townhomes along the Expo Line, just east of Crenshaw, the Amalfi Apartments, 67 market-rate studio, one- and two-bedroom apartments (and seven units reserved at the Very Low-Income level), located on Stocker, just a block south of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, and a handful of affordable housing projects all along Crenshaw (see here, here, here). And the four buildings comprising Stocker Plaza, just west of Crenshaw, were just purchased by Sharp Capital Group at the beginning of the year; no word on plans for them, yet.

The area's dwindling black population is literally seeing development crop up all along its perimeter, in other words. And given the trend toward gentrification along other transit lines, it can probably expect to see more in the not-so-distant future.

To be fair, many of these developments are both welcome and long overdue. The Marlton Square site had languished in redevelopment hell for decades, thanks to the size of the site, the multiple owners that made it hard to cobble the parcels together, the redevelopment regulations that limited the income that could be earned on the property and, later, the dissolution of the CRA that made it harder to direct how the property would be developed. The District Square project ran into some of the same problems the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza has seen over the years - a major retailer pulled out shortly after the project broke ground. It was originally intended to have been completed in 2013 and feature retailers like Target, Ross, Smart & Final, and chain eateries. When it finally gets off the ground again, the current project will feature a downsized retail component and approximately 200 units of housing.

But these projects are happening all at once because South L.A. has finally become more viable for investors. Which means that while, together, they have the potential to raise the profile of the area in the way that residents have been clamoring for for decades, they are also likely to give the area the kind of boost that renters and smaller businesses do not have the resources to weather. The result could be an accelerated loss in both African American residents (those pushed out and those unable to afford to move in) and African American-owned businesses, as the displacement of one feeds the displacement of the other.

The loss of the black population, the potential for indirect displacement, and the harms of gentrification - things that have a significant impact on the well-being of communities and the overall health of our fair city - are rarely meaningfully addressed in public hearings. We don't have a way to incorporate the richness cultural communities contribute to our urban fabric into planning calculations or a mechanism by which we can examine the qualitative impacts of larger development processes in a meaningful way. The Environmental Impact Review (EIR) process only allows for the assessment of direct displacement by a project, for the most part, making it very easy for planning staff to dismiss outright any concerns residents raise about indirect impacts in their reports and during hearings - something I've observed them do on more than one occasion.

Yet, should planners have a question about whether the presence of construction workers might overburden a public library located two miles away from the job site, they can refer to the full two and a quarter pages of the staff report on the EIR dedicated to the exhaustive contemplation of that highly inconsequential topic. [Full report is here; the library discussion begins on p. F-83.]

Housing proponents will no doubt find a call for the examination of the indirect effects of development troubling and argue that development is already hard enough as it is. Which is not necessarily untrue, especially in here in Los Angeles.

But the history of the mall speaks to the larger history of the community and the importance of a reckoning for all the indignities it has endured. Had the community not seen such abandonment by whites and such profound public and private disinvestment, some of its areas would not be so ripe for "reimagining" and "revitalization" now, nor so potentially lucrative to investors and home flippers alike. And if the abandonment of the urban core hadn't gutted funding for schools and services and pushed opportunities for upward mobility so effectively out of reach for so many, the sizable percentage of residents that remain on the margins there today would not be so vulnerable to displacement.

Disenfranchisement was by design, and it has exacted a tremendous, multi-faceted toll.

It follows, then, that the community is owed a better understanding of what the larger implications of pending projects are for the area, at the very least. When we stick to spot planning and ignore the larger context, it is hard to engage in more creative thinking about how to leverage projects in ways that enhance the ability of disenfranchised residents to remain in place and contribute to the vision of the future of the area.

And when there is no space to discuss how to safeguard vulnerable communities, we are more likely to see what played out during the Reef approval process: namely, neighbors subjected to so many of the same hardships pitted against themselves.

Those that decried disinvestment for decades shouldn't have to wonder whether the belated arrival of investors signals the beginning of the end for their community. Yet, they can't afford not to. And if we value a city that is rich in people, culture, and community, we can't either.