As far as equity, everyone has a very different definition of equity.

Wait, what?

If you ask the folks in South Orange County, they say, 'We’re not having equity. [We’re] investing $350 million in the streetcar in Santa Ana—where’s our $350 million?'

You can't be serious . . .

When you’re asking people in Santa Ana about the streetcar, what that means is issues around property . . . those are market driven issues that will be what they will become.

Please, don't.

I think the urbanization of our county is changing regardless of whether there’s a streetcar project there or not. And those issues around property valuations, and property taxes--those are going to be there regardless. This may accelerate it in some way, but it’s going to occur no matter what.

. . . sigh . . .

Let's back up. This was at October's Orange County Active Transportation Forum in Garden Grove, and the quotes above are from Darrell Johnson, CEO of Orange County Transportation Authority. It was the first session of the morning, and leaders from other agencies—including the Orange County Council of Governments, Southern California Association of Governments, and Caltrans—shared the stage with Johnson.

The talk was initially pretty optimistic: Caltrans District 12 Deputy Director of Planning Lan Zhou discussed the state's effort to create an Active Transportation Plan, SCAG Executive Director Hasan Ikhrata showed off the local results of its GoHuman campaign in Westminster and Garden Grove, and OCCOG chair Marika Poynter presented its OC Complete Streets handbook, a guide for cities to implement Complete Streets ideas.

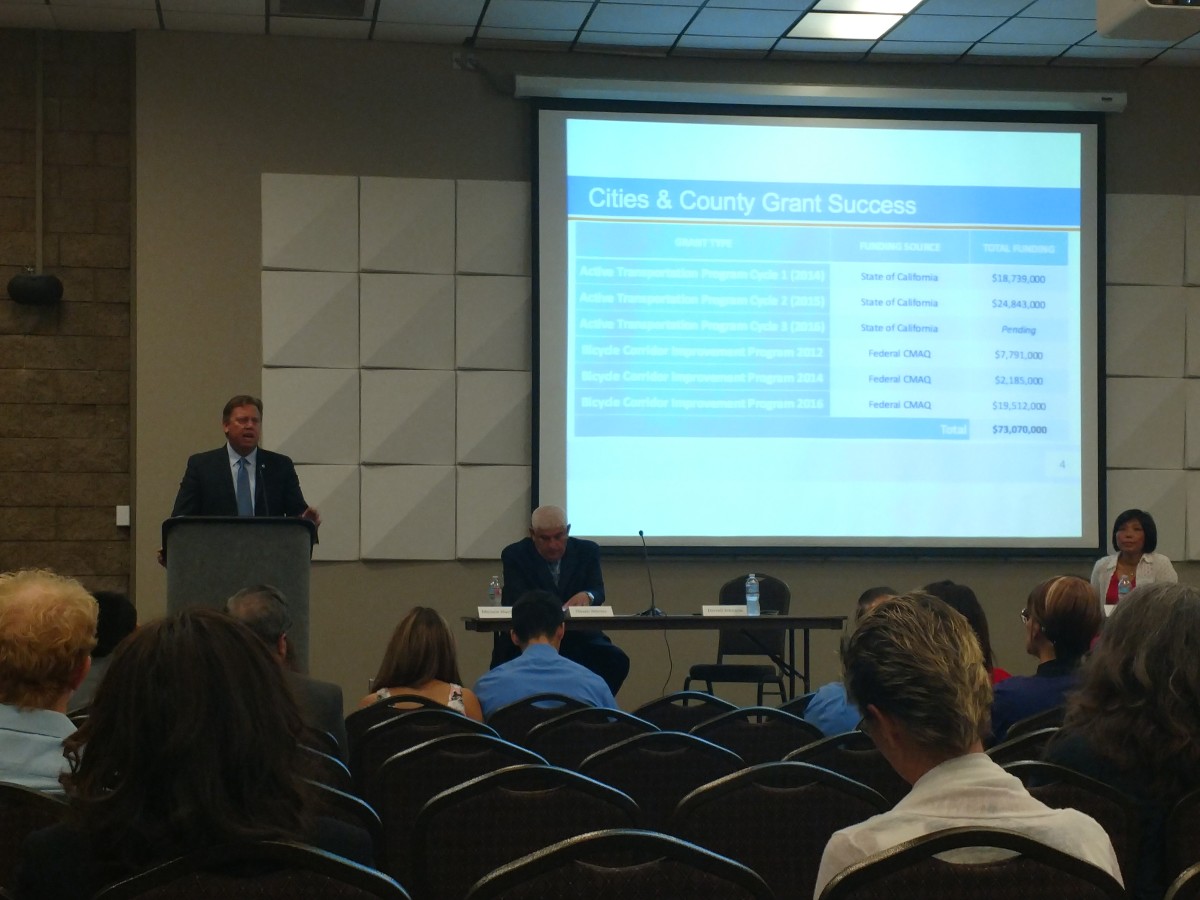

The positive outlook extended into Johnson's presentation. He talked about OCTA's efforts to make streets throughout the county more multimodal. He highlighted the more than $73 million OCTA received from federal and state funds for bicycle/pedestrian projects, the sixty percent completion of the 500-mile Regional Bikeways Network, and the agency's planned start next year on a countywide active transportation plan.

But a question from Marina Ramirez, a Santa Ana resident and member of Santa Ana Active Streets Coalition, put Johnson on the defensive. She asked the panel what is being done to address displacement from active transportation improvements. She added a followup question: OCTA has an active transportation checklist, she said; why not add an equity checklist?

Johnson avoided the question and said it was not OCTA's responsibility to consider equity. Instead, he explained that housing, jobs, and population are all expected to increase over the next twenty years. "I think it's important to talk about the big picture for the moment and then narrow it down," said Johnson.

We live in a county with 3.2 million people, and based upon the plans that are submitted to OCTA and through SCAG about the future, over the next twenty years—through no doing of OCTA—we’re told that we’ll see housing increase by 13 or 14 percent. Population will increase by about the same, and jobs will increase by about the same. When you model all that together we see congestion in our county at all modes increasing by about 165 percent.

Then Johnson revealed that he sees OCTA's job as solely relieving congestion—and that he believes OCTA has no business dealing with equity. "Our job is to figure out how to address the 165 percent [increase]," he said.

That’s going to take a whole variety of things. That’s going to take better bus services, better streetcar service; it’s going to take better Metrolink service, better Active Transportation. But there’s no one-size-fits-all, so we want to work through [in whatever manner it takes].

When he tried to come back to the question, his answer slid into a new realm of misunderstanding:

A recent example: the City of Santa Ana has asked us to look at some removal of lanes on a highway.* This idea of taking out a lane in traffic and replacing it with active transportation is an idea that they have. It’s an idea we’re not opposed to, but an unintended consequence is the severe impact on the frequency of transit service on that corridor. So we’re taking people that are used to riding the bus, making a trip from point A to point B in 30 minutes, and because of the increased traffic congestion [from reducing the number of lanes], that 30 minutes becomes 90 minutes or 80 minutes.

Johnson seemed to be talking about the proposed protected bike lane on 17th Street, which currently has between six and seven travel lanes. In its recently adopted Safe Mobility Santa Ana plan, the city of Santa Ana is proposing to remove one travel lane in each direction and add protected bike lanes. Such road diets have not been shown to increase travel times, and it's not clear that this one would affect transit riders, as Johnson claims. Besides, OCTA has a lot more to worry about with its recent history of record declining bus ridership than a bike lane that could actually complement bus transit.

As far as equity, everyone has a very different definition of equity.

For kicks I looked up a definition of transportation equity from the Center for Social Inclusion: "Accessible, affordable transportation is critical to the lives we live. . . . Too often competing interests result in transportation policies that unintentionally leave low-income Americans stranded. To achieve equity in transportation policy, we need to craft and catalyze strategies that help rural and urban communities of color get the investments needed to spur mobility in every sense of the word."

Here's Johnson's definition:

If you ask the folks in South Orange County, they say, 'We’re not having equity. You’re investing $350 million in the streetcar in Santa Ana. Where’s our $350 million?'

First: comparing North County with South County is irresponsible. UC Irvine's Community and Labor Project and UCLA's Labor Center published a study in 2014 showing that North and South Orange County differ in multiple ways. The North has the highest number of renters, is the densest—it's important to note that Santa Ana is the densest city in the county and the fourth most dense in the country for populations above 300,000 people—has the largest population of low-income earners, and is the most ethnically diverse.

South County, meanwhile, contains the majority of the wealthiest citizens in the county, and has the largest white population. Of course there are outliers—I'm looking at you, Yorba Linda—but as the most recent election breakdown showed, the region's demographic and political ideologies are split.

When you’re asking people in Santa Ana about the streetcar, what that means is issues around property

It's a little more complicated than that, but property, specifically concerns about gentrification, is being brought up by residents.

Those are market-driven issues that will be what they will become. We’re working hard to ensure that when construction activities occur, the businesses and community know what they are. Then the built-in becomes a part of their community. And there's been broad broad support in Santa Ana and Garden Grove community for this next step and looking at what that is.

This last is not entirely true, as businesses in Santa Ana opposed the portion of the streetcar route that cuts through Fourth Street).

So we’re trying to accommodate the current needs and the needs of the future.

Johnson is ignoring a body of research that shows the connection between TOD and gentrification.

OCTA, unfortunately, is like the many transportation departments across the country that stay in their lane when it comes to their projects. But that focus ignores research that's shown the role of transit corridors in reshaping demographic landscapes. Here's a taste: UCLA created a mapping tools that show gentrification happening along transit corridors, and the National Institute for Transportation and Communities last year published a report showing the relationship between jobs and real estate with transit like streetcar, light rail and bus rapid transit.

The first Untokening Conference, which happened last weekend, brought people from around the country to talk about how communities of color are the most affected and disenfranchised when it comes to transportation "investment." For them, the focus on transit it ignores other ills that plague their communities like unemployment, truly affordable housing, and lack of access to capital for small businesses. Sometimes the same infrastructure can compound their communities' problems, bringing things like rent increases and increased negative attention from police.

SCAG's Ikhrata backed up Johnson's words, but his answer showed that at least he was making the connection between gentrification and transit and was much more sympathetic to folks displaced by a City's changes. "I think gentrification is an issue that our society and our region needs to deal with," Ikhrata said. "There is no perfect solution out there, but I think we do need to make an effort to make sure that whatever we do we don’t make it difficult for the people who live there all their lives."

(All the presentations are available on the Alliance for a Healthy Orange County website)

* Note: OCTA uses the term "secondary highway" for major streets, which tend to be large, six-to-nine-lane roads.