The Safe Mobility Santa Ana Plan was released earlier this month with very little fanfare, yet it may be the planning document that will possibly have the biggest impact on the city's streets for years to come.

The plan identifies 42 high-priority projects–37 corridors and five intersections–that would take an estimated $40 million to complete.

But most compelling is the language in the plan that hints at a culture shift in the city away from motorist convenience and towards a focus on pedestrian and bicyclist safety.

Current planning in the city relies on regional guidance as laid out in the Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) Master Plan of Arterial Highways (MPAH). Cities are supposed to make sure their plans are consistent with the MPAH, or risk losing local sales tax revenues. But the new plan boldly claims:

With a focus on safety, many of the recommendations in the Safe Mobility Plan are not consistent with the current MPAH.

And that's okay with the city. Instead of focusing on vehicles, as the MPAH does, the Safe Mobility Santa Ana Plan will either reclassify streets to align better with bicycle and pedestrian safety, or remove them from the MPAH system.

Talk about whoa. While previous active transportation projects have requested that roads be reclassified in the MPAH so as to redesign them, this may be the first city document to outwardly proclaim it plans to do so routinely.

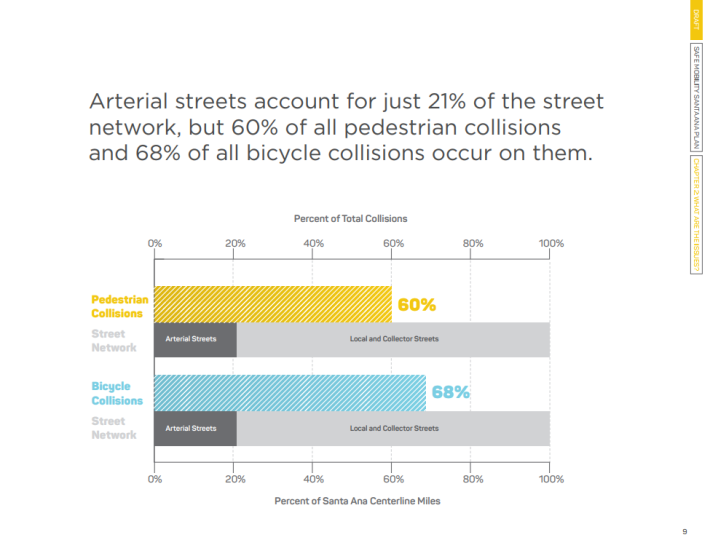

The City's main arterial streets will see much of this change, as they have been the ones identified as having the most collisions. Some notable projects:

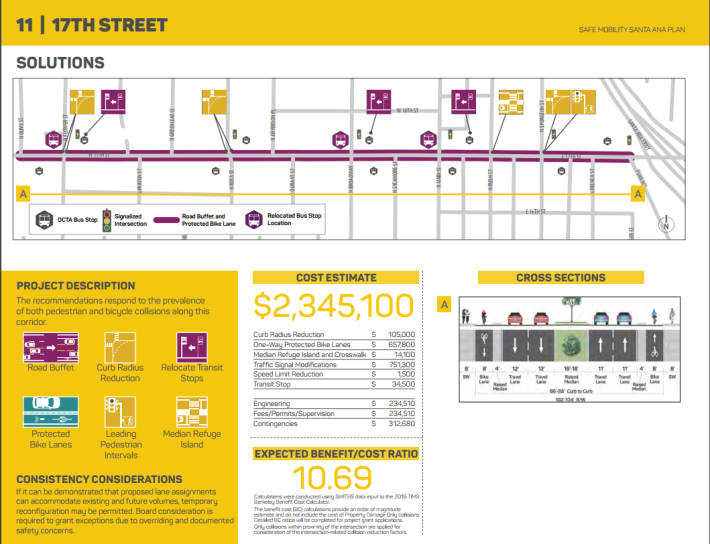

- 17th Street, currently six travel lanes, would be narrowed to four lanes and add an eight-foot protected bike lane.

- First Street, currently six travel lanes, would be narrowed to four lanes, add a seven-foot protected bike lane and add median refuge islands at two intersections.

- The contentious Warner Avenue Project–about which we've written in a prior posting–would include a widened sidewalk on the north side of the street, four ten-foot travel lanes, and a five-foot-wide bike lane.

The city's Public Works Agency was in charge of completing the plan. I sat down with Fred Mousavipour, Public Works' executive director, and Cory Wilkerson, the Agency's active transportation coordinator to go over the details. The conversation that follows was edited slightly for clarity and length.

How did the Safe Mobility Santa Ana plan come to be?

FM: We've been working on it for about a year and a half, and it really got into high gear after the unfortunate accident with three girls on Halloween night on Fairhaven and Old Grand. We got direction from the Council and the City Manager to really start emphasizing the safety of pedestrians and bicyclists in Santa Ana. That's when we went ahead and hired one of the best consultants in the field, NelsonNygaard, to come up with a Master Plan showing where we are, where we want to go, and how we want to get there.

Where have you presented the plan so far?

CW: We've spoken with Santa Ana Business Council, the [Downtown Santa Ana] Restaurant Association; I spoke last night very briefly on it as part of a bigger presentation on active transportation stuff with the Artesia Pilar, Floral Park, and Washington Square Park neighborhoods. We have it scheduled to go to the planning commission in October and I've been working with Nancy [Mejia, Latino Health Access director of community engagement and advocacy programs] to get it scheduled for Building Healthy Communities or any other nonprofit organizations that we can meet with and go through a presentation.

We want to make sure that the folks that have been the most interested and the most vocal about these issues are getting an opportunity to hear about what we've done and what our plans are to go forward.

How does the Safe Mobility Santa Ana plan work?

FM: This study would basically evaluate all the circumstances around collisions involving bicyclists and pedestrians and come up with causation and remedies using the three factors of enforcement, education, and engineering to resolve every one of them.

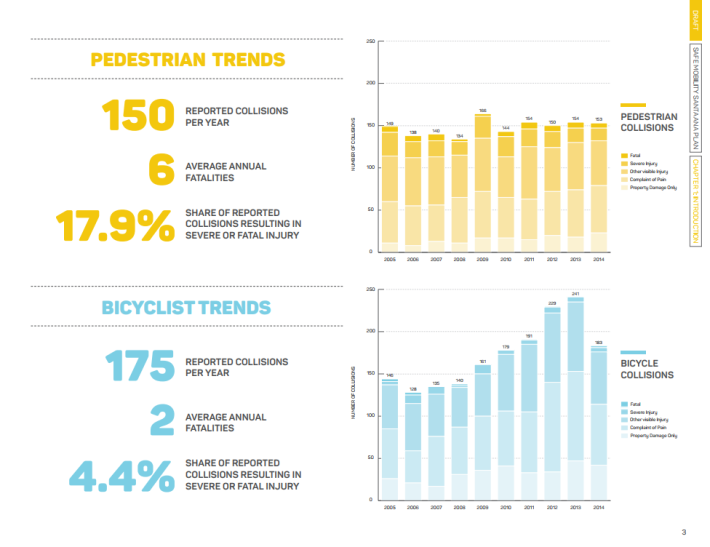

What's interesting about Santa Ana is that we're the fourth most densely populated city in the United States, and we have a high ranking, unfortunately, in terms of fatalities and severe injuries here in Santa Ana. It's kind of an epidemic. Every month you see an accident, unfortunately. Just yesterday somebody got killed over at Santa Ana Boulevard. It's kind of getting predictable where the areas are that these things happen.

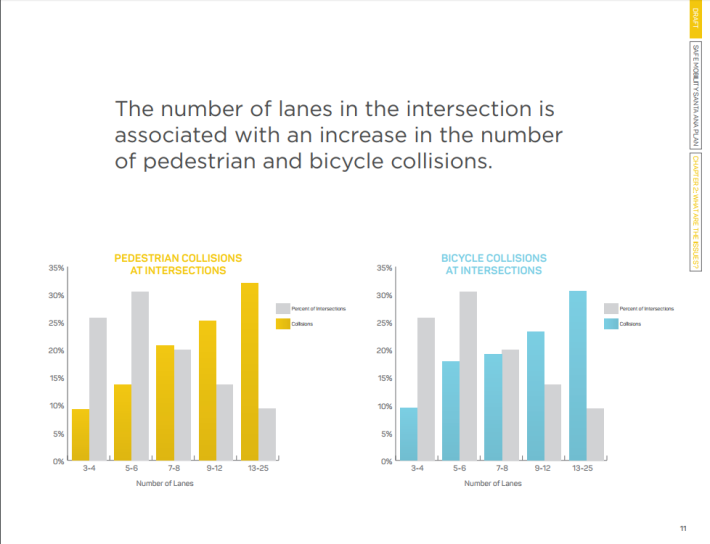

CW: The difference between a minor injury, a major injury, and a fatal injury is speed; it always plays a factor. Even if it's not listed as the collision factor, it always plays a factor in how severe the collisions are. Statistics show that streets that have higher traffic volumes, more lanes, and higher speeds are the locations where we are seeing the highest amount of severe fatal collisions.

There are six corridors where we're seeing the most collisions, and those are all pretty much our arterial networks, so we're trying to address how we make things safer there. I think the top thirty projects address about 46 percent [of collisions] citywide. So if we can solve those corridors we can cut the number of collisions by half.

The goal is ultimately zero–it is a Vision Zero plan.

Why is it called "Safe Mobility Santa Ana Plan" and not "Vision Zero Santa Ana"?

FM: We didn't call it Vision Zero because Santa Ana has its own characteristics and its own issues. We wanted to customize this plan to Santa Ana. One of the reasons is that 55 percent [of the city's population] don't have cars, 52 percent are under the age of 30. We wanted not to confuse it with a one-size-fits-all concept.

CW: I saw a presentation by Leah Shahum, who’s the director of the Vision Zero network. She said she prefers the term Safe Mobility to Vision Zero. She likes it because it’s more accurate and it looks at things more holistically.

One of the things about the language throughout the plan, even in the first few pages, is that it really feels like the philosophy in the city is changing. It’s not "road diets"; it’s "road buffets." Even when it’s addressing OCTA’s Master Plan of Arterial Highways, the plan says that it may at times go against OCTA’s vision. In developing this plan, what was the process to bring all stakeholders on the same page to achieve this?

FM: We're pretty much in alignment with the police department, because they're our partners and we've been working with them from the beginning.

We have engaged in conversations with Orange County Transportation Authority, because they need to be our partners. As you know, Santa Ana is sitting in the middle of Orange County. So people going through the county want to take the streets–what OCTA calls the secondary highways–and we have huge traffic passing through Santa Ana. Historically, OCTA has been concerned with the movement of traffic and congestion. Our concern is safety. We're partnering with them to close that gap and come up with a solution that addresses their regional issues and at the same time protects our residents on these main arterials.

CW: We don’t want to be out of compliance with the Master Plan of Arterial Highways. What we’d like to do is take the corridors that are in the MPAH and reclassify those corridors to allow ourselves more flexibility in how we can configure that roadway.

We met with OCTA two weeks ago to talk about it. They’re very sensitive to safety; they recognize that it’s very important to us. According to them, this is the largest reclassification all at once.

If we slow down traffic on a corridor, that has the potential to slow down some of the transit operations. They want to make sure that those [issues] were being addressed. So we met with them to start some early discussions on how we can mitigate some of these issues and work with them. We’ve just begun that process.

The city has also been updating the Circulation Element. And our Planning Agency has been very kind in slowing down that process so we can complete this safe mobility plan and incorporate some of it into the Circulation Element–like the reclassification of some of our arterials. The conversations have been positive, and we definitely have felt this is all reasonable and stuff we’re going to be able to accomplish.

FM: We’re talking about being reasonable, but we’re going to be unreasonable about making sure that we reduce the collisions here in Santa Ana. Right now we are reducing speed limits in a number of critical areas to 25 miles per hour, including an entire business district in the downtown area. And on top of that we’ve put our top-notch people on writing grants to get money brought over to implement this program from the state and federal side.

CW: It’s been like $30 million in the last two years.

FM: Unprecedented, the amount of money . . .

CW: For a city of our size, yeah . . .

FM: Unprecedented. We think once we have our Master Plan approved by Council, which I expect it will, we will be better positioned to bring in more funding.

CW: Sometimes with grants, it's about being competitive, and the SMSA plan will continue to make us competitive as we lead the pack for Orange County. It’ll give us that extra tool to continue to be competitive and provide a more multimodal transportation network.

FM: So we’re putting in all these bike lanes all over the city–green bike lanes, dedicated bike lanes; we will have Class IV, which is completely separate, protected bike lanes. We’re working toward connecting the train station to downtown using bike-share and Zipcars. We’re narrowing lanes. In downtown, if you have seen, we’ve put a lot of bulb-outs. We have done things that have proven–we have done the testing–to actually reduce speeds.

CW: When we resurfaced Harbor Blvd., we [made every travel lane] ten feet–that's the minimum lane width you can get away with. The goal is, by reducing the width of the lane, to force cars to slow down. In some places that resulted in us being able to put in a buffered bike lane. Some places we only got a four-foot shoulder, but all the lanes now are narrowed down to ten feet. We took "before" speed counts, and now we’re comparing those to recent "after" speed counts. Our goal is to slow cars down citywide as best as we can using all the engineering tools, enforcement tools, and education tools we have at our disposal.

Road buffet. What is it and where did the inspiration come from? It’s used in the plan to describe what I usually understand as road diets, so how does the term you use differ?

CW: Nobody likes a diet. Nobody likes the word diet. Any time you use that word when you’re reaching out to the community, you immediately get faces grimacing.

I stole that term from a gentleman up in the L.A. area, he kinda said it in a joking manner, but it really made a lot of sense. It’s about creating choices for everyone. So we decided we’re not going to call it a road diet–it’s a road buffet. I think that it really does accurately depict what we’re trying to do, reconfiguring streets rather than taking something away.

There’s an emphasis on enforcement. More enforcement can lead to profiling, especially in communities of color. How does the plan address this?

CW: Our traffic enforcement officers spend a majority of their time responding to collisions and writing up collision reports. It’s reactive. A collision happens, they go out there, they spend a few hours trying to assess what happened–rather than proactively enforcing speed limits or responding to issues that are happening.

The plan says: this model of investing so much time and energy responding to collisions isn’t allowing us to do the proactive work that we need to do. The plan centers around increasing opportunities for our officers to do enforcement. It also recommends additional enforcement officers to allow them to go out and saturate specific areas where collisions are happening. We know where the highest priorities are, and those are the areas where we want to do the most proactive enforcement.

It’s not about profiling except that it’s about focusing efforts in areas where we’re seeing collisions happening.

There’s also an education component. Some of these programs may provide information rather than punitive tickets. When [the police] do sting operations, it’s not always a punitive thing, and they're open to ideas.

Although sometimes the punitive stuff is necessary–that is often a way to change behavior.

FM: We’re gonna have to do the engineering treatments that discourage dangerous behavior. It’s our responsibility to make sure we do what we can to discourage those kinds of behaviors anyways, before we get to enforcement. That’s our first goal.

Our second goal is education. We want to start with the schools–we’re going to teach kids so they can teach their parents about safety. That’s specific to Santa Ana.

And then at the end would be enforcement. For instance, people here have a habit of crossing mid-block. We get a lot of injuries and fatalities from that. So we need to think about, first of all–before we start having police giving people tickets–we need to have extra lights, we need to have extra crosswalks, we need to put barriers in the middle of the busy streets to discourage people from crossing.

And then if somebody wants to break all of these things, and run through and jump the fence, then maybe they need to get ticketed. That’s what makes it different than "let’s go out there and start ticketing people." We don’t have any intention of doing that at all. It's the worst way of spending our resources, and creates a situation that we don’t want to create here.

We’ve been talking about behavior quite a bit, but how will the plan prioritize projects and areas?

CW: The plan definitely identifies the key causes of collisions by location. What’s happening on Main Street is not the same thing as what's happening on Bristol Avenue. There are different behaviors; engineering recommendations at those two locations are different.

On Main Street, we’re creating more opportunities for pedestrians to cross. On Bristol, we’re working on providing a protected bicycle facility that gets bicyclists off the sidewalk. In other locations we need to put in more crossings or median refuges. There are different treatments at different places; it’s not really one-size-fits-all.

FM: We’re not going to use people’s habits as an excuse to blame them. We have a responsibility to make the street safe. And we have every intention of doing whatever we need to do first to put those features in place rather than say they shouldn’t have gone fast, or they shouldn’t have crossed the street, so it’s their fault, we don’t have to worry about it. If we were going to do that, we wouldn’t have to do anything.

CW: Look at what causes those behaviors. Like: why does a pedestrian cross mid-block? Because they have to go a quarter of a mile to cross at the signal and then come back a quarter of a mile; they just added a half a mile to their walk.

What’s the biggest cause of bicycle collisions? A lot of it is the bicyclist riding on the sidewalk. Why do bicyclists ride on the sidewalk? Because there isn’t safe infrastructure on the street for them to be able to ride there.

So those are things that we can address. We can increase the number of pedestrian crossing points. We can increase the number of protected bike lanes, or buffered bike lanes, or whatever makes sense on the corridor we’re looking at. We can implement those sorts of things and then say, how does that affect behavior? Do we need to do more? Is there more enforcement that needs to be done? Is there more education that needs to be done?

FM: Education also becomes very important because . . . people don’t know. If they had all these statistics of how many people are killed and injured on a weekly basis, they would be more careful. Because they don’t know the information, they don’t know how dangerous it is to ride on the sidewalk or cross mid-block. So education by itself becomes important.

We’re just going to try to reduce this thing one at a time. One injury, one accident at a time.

CW: Not accident, collision.

FM: Every week that I get a report, from the fire department or police department, I get them right when it happens. It’s personal. It’s a priority. So we’re going to do whatever we can to reduce all these things and bring the numbers to as low as possible.

CW: Zero.

FM: And we’re going to be successful doing that, because we’re committed.

Is this plan too ambitious? Why not do more pilots first, ease ideas in? Especially with the city’s recent history of widening streets and designing streets for cars, are you sure the plan is not being set up to fail because of its lofty ambitions?

FM: First of all, we can’t afford to slow down in Santa Ana because as I said we see the reports that are coming out, too many people are getting injured.

CW: It’s like 34 severe or fatal collisions every year.

FM: That time is past. This should have been done thirty years ago, and it wasn’t. We’re in a fight to get things done as fast as possible.

And we are testing. The last year and a half, two years, we narrowed lanes, we measured the speed; that’s why we were able to legally lower the speed to 25 miles per hour. We’re putting in bulb-outs, bollards, the medians. We’re looking at all these things, and we’re incorporating the results into our master plan.

To address something about widening: road widening is done to move volume–a lot of cars. It doesn’t mean you have to move a lot of cars with the fastest speed–that was the old idea. The intention is to move the volumes uninterrupted. You can do that by having the right design.

CW: The design has a huge impact. For a motorist, if you’re driving at thirty miles an hour, but you’re not stopping at every single stop light, you’re going to have a less stressful drive and you’re going to get there faster. If you’re punching it and then stopping . . . it creates an aggressive feeling as you’re driving, it’s a stressful drive.

We’re not opposed to pilots. Pilots are great. Pilots in my world is an outreach opportunity which is going to help me write a better grant application when the time comes so that we can make it permanent. Look at what we did on Ross Street: they resurfaced the street; we put in buffered bike lanes. That’s not the final product, though. We still want protected bike lanes out there. We’ll put in a buffered bike lane as a placeholder until we can get more funding to put in the protected bike lane. That’s our idea of a pilot project.

Anything else you’d like to add?

FM: I just want to let everyone know this is one of our highest priorities in Public Works and also city council.

One of the fundamental differences between this community and others is that in a lot of other places in California they try to put nice sidewalks and bike lanes to encourage people to use the bike lanes to dump their cars, to use the bus, to change their mode.

Here, the bikers are there by necessity. They have to go to work. People on transit, people who walk on sidewalks and take transit, who cross the street, who walk with their kids–they’re already there. That’s why this is critical. We don’t have time and luxury to test these things. We need to provide this infrastructure for them, that’s the reality.