The Active Transportation Program is California's main source of funding for projects that encourage walking and biking. Caltrans just closed the third round of ATP grants on June 15, and will allocate $240 million for projects—beginning three years from now.

That may sound like a lot of money, but compared to the state's overall transportation budget of over $10 billion, it's a drop in the bucket. It is also taking a long time to happen. Currently more than 500 ATP projects are in the pipeline, either planned and waiting for approved funding or being built. But California needs better biking and walking facilities on the ground now if Caltrans really wants to reach its goal of tripling bike trips and doubling walking trips by 2020.

Meanwhile local planners, with limited time and funding, navigate the complex application process for the ATP grants. In June, Caltrans received 452 applications for this third round of funding. The two past cycles saw larger numbers of applications being submitted: 717 for Cycle 1 and 612 for Cycle 2.

Turlock, Modesto, and Tulare County were three of the Central Valley jurisdictions that submitted applications in this round. Turlock and Modesto made only one proposal each.

In Turlock's case, city staff conducted a series of outreach meetings to find out what residents wanted, and that effort yielded a variety of project ideas. Staff ultimately chose to focus on a single project: pedestrian improvements near two elementary schools.

The proposed project focuses on pedestrian accessibility near Wakefield and Cunningham elementary schools, including curbs, gutters, sidewalks, curb ramps, and high-visibility crosswalk striping. The application also incorporates a non-infrastructure component that would focus on education, encouragement in the form of walking and biking maps, and an enforcement campaign.

Wayne York, transportation engineering supervisor, said the education piece is not clearly defined yet, but the application called for hiring a consultant to work on engaging with school district staff to conduct safety training. For the enforcement piece, he said Turlock police would focus on right-of-way violations against people on foot and on bike.

The city is seeking $1.5 million in ATP funding towards the total project cost of around $1.8 million.

In the last round of funding, Turlock successfully secured more than $1 million. Staff attributed their success to a strong public outreach campaign that helped shape the project design. They replicated their efforts this round by soliciting feedback through utility bill inserts, social media, and public workshops held at various parts of town.

York said that once staff had a good sense of what the community wanted, they designed the projects that would have the best chance at scoring the highest number of points on the ATP application. Unfortunately that meant leaving out some stakeholders out in this round of funding.

“During the most recent public outreach there was a stronger response for projects by bicyclists,” York wrote in an email. However, he said, the last successful application had addressed some bicycling concerns, and staff also took into consideration the sentiment from some residents that it was important to “fix what we have before you install something new.”

The lack of bicycle-related projects for Turlock is also due to the ATP process itself.

Although cities can submit multiple applications, York said the complexities and demands of the whole ATP process impacted his office’s ability to craft more submissions.

For instance, many of the bicycle projects the city was considering would require right-of-way components. Under the ATP process, the city would need to get letters of support and/or concurrence from other property owners. York said that city staff didn’t think there would be enough time to gather the required permissions, “so focus was shifted to projects that did not require right-of-way acquisition.”

He added that while the application form itself has improved, demands have increased over the last three years, impacting his ability to craft more submissions. Not to mention that the work he and the rest of the staff have done on the application is non-billable.

“It is an extremely time-consuming, resource-intensive process,” he said.

In Tulare County, Kyria Martinez, the county's economic development analyst, agrees that it is an intensive process and that it gets more complex every year. In spite of that, however, her team was able to submit applications for twelve ATP projects this year.

Martinez said she and staff leveraged work that was already underway. The county’s Safe Routes to School plan, for example, includes a large outreach component that was a good candidate for ATP funding. In fact, all twelve projects came straight from the SRTS plan. Similar to Turlock, Tulare's projects focus on sidewalk improvements around mainly rural schools around the county.

Martinez said having someone who has experience writing grants on the application team alongside engineers helped them do a better job on some of the detailed sections about project goals and purposes. “I would just sit down with them and say, ‘Okay: How is this going to improve the community?’ and we would write it together,” Martinez said. “That is sometimes hard for engineers; they don’t often think that way.”

She added that even though the county’s SRTS plan helped them craft the best submissions possible, additional requirements like crash data, which they don’t have readily available, will probably cost them points.

“There was a lot that we had to do that was very difficult for us,” she said.

Tulare County is one of the few agencies in the Central Valley that submitted more than one project application for ATP funding. Others, like the city of Modesto—which has recently been improving its bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure—chose to submit an already identified project that was in its existing non-motorized plan.

“We didn’t have the energy for more than one,” said Michael Sacuskie, associate engineer and bicycle program coordinator for the city.

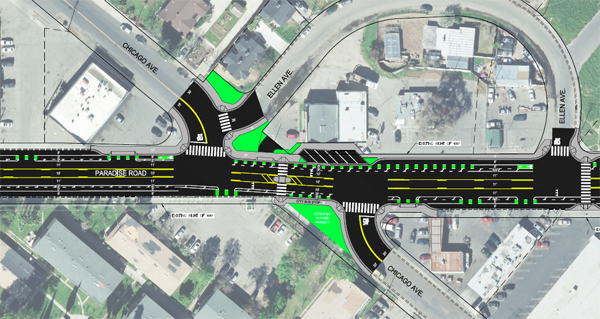

The Modesto project, a road diet on Paradise Road from First Street to Sheridan Street near Modesto High School, had been already assessed for safety impacts by the Institute of Transportation Studies at University of California, Berkeley.

City staff also conducted extra outreach to gather input from the Modesto High School community and local residents, and the Stanislaus County Council of Governments' Bicycle/ Pedestrian Advisory Committee submitted a letter of support.

He said the proposed project is the “candidate of candidates” for ATP funding. Paradise Road is a busy road in West Modesto with wide lanes and skewed intersections that has been the scene of many collisions and fatalities. The neighborhood has a large number of residents that bike and walk as their main form of transportation because they have no other choices.

But Sacuskie, Martinez, and York all lament that if more requirements are placed on ATP applications, their communities could lose out because only large agencies with plenty of resources would have the capacity to apply for ATP funds.

This is one of the reasons the California Bicycle Coalition is sponsoring a bill, A.B. 2796, to require that at least five percent of ATP funding be set aside for planning in disadvantaged communities. If cities can't plan projects, they can't apply for grants to build them.

“It seems that when there’s bicycle and pedestrian funding, it’s so difficult to receive,” Sacuskie said. “To me that's counterintuitive. There could be a simple process.”