After some delay and a surreal debate, a bill that could help create affordable housing by easing parking requirements passed the Senate Transportation and Housing Committee on Tuesday on a 7-4 vote. Now it goes to the Committee on Governance and Finance, where it will be heard as soon as next week.

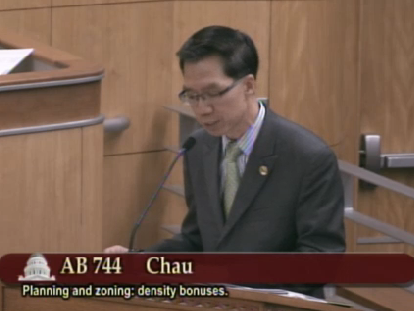

The bill, A.B. 744, would reduce parking requirements for affordable housing developments, making it less expensive to build affordable housing and using federal tax credits to build housing rather than unnecessary parking.

Some of the senators on the transportation committee showed a deep misunderstanding of the effects of parking policies, as well as of the larger purpose of the bill. They told anecdotes about spillover parking, asked about what happens after the entitlements run out after fifty years, and complained that the bill would take away local decision-making power and give it to profit-seeking developers. “There will be many unintended consequences of this bill if it passes the way it's presented,” concluded Senator Patricia Bates (R-Laguna Niguel) with disapproval before voting no.

But the purpose of the bill is to fix existing unintended consequences of current parking requirements. Those consequences include unnecessarily high construction costs that make affordable housing infeasible to build, thus exacerbating an already dire shortage of housing for low-income people.

The bill's author, Assemblymember Ed Chau (D-Monterey Park), had to repeat several times that A.B. 744 is targeted at a very specific type of housing: for people who either cannot afford a car or are not likely to drive. It would reduce the number of required parking spaces in new housing developments that provide 100 percent affordable units and either:

- have unobstructed access to a major transit stop within a half mile

- are for seniors

- are for developmentally disabled adults

Senator Cathleen Galgiani (D-Stockton) may have had the most difficulty understanding what the bill was about. “I'm having trouble with the idea that as a senior, I could only have half a car,” she said, hopefully with tongue firmly in cheek. Chau explained that the number of spaces required by the bill—0.5 parking spaces per unit—was an average based on an estimate of how many low-income senior residents would need a parking space. That is, some wouldn't.

Finally Senator Bob Wieckowski (D-Fremont), who had been squirming in his seat during much of the discussion, spoke up. “I applaud you for bringing this bill,” he said to Chau, “because there are dozens of tone-deaf, bitter city councils that are using parking requirements to not allow affordable housing to be built in their communities, and somebody needs to say that.” City councils throughout the state of California, he said, need to “get the message that we need to move forward and stop playing games with parking requirements.”

The bill had already gone through the mill in the same committee last week.

At that hearing, the League of California Cities, saying they “were not against the premise of the bill,” proceeded to object to everything about it. When Senator Ben Allen asked the League's representative, Dan Carrigg, how the bill could be amended to satisfy the League, Carrigg asked for specific benchmarks. “A new baseline that matches each project,” he said. “Define the types of projects, look at the level of parking required, then establish a reasonable benchmark.” That way, he said, “there will be less controversy from the community.”

So Assemblymember Chau came back this week with an amended bill that included specific numbers. Instead of requiring local jurisdictions to eliminate parking requirements entirely if requested by a developer, as originally written, the amended bill sets a parking ratio for each type of housing it is targeting. That is:

- Affordable housing with unobstructed access to a major transit stop within a half mile could require no more than 0.5 parking spaces per unit

- Senior housing within a half mile of a major transit stop or that provides paratransit could require no more than 0.5 parking spaces per unit

- Developmentally disabled housing within a half mile of a major transit stop could have no more than 0.3 parking spaces per unit

In addition, if the local jurisdiction strongly believes it needs to require more parking, it could use a parking study, completed any time within the last seven years, to bolster its case.

But the League was not satisfied with the amendments, and wanted higher minimums. “We don't think seniors are giving up their cars,” said Carrig. “Potentially not having enough parking might put a senior in the position of deciding to get rid of a car in an area where they don't have access,” he said. He raised the specter of spillover parking taking up all the existing street space in neighborhoods surrounding new developments. “We want to test the thresholds against more practical reality.”

This last point could have been a good one, except that current parking requirements--as explained repeatedly by UCLA Professor Donald Shoup [PDF]--are based on arbitrary numbers backed up by nonexistent data. In contrast, the parking ratios Chau used in this bill are based on the practical experience of sponsor Domus Development, an affordable housing developer, as well as on data collected by TransForm on parking in housing developments that sits unused.

Here's some real data about the types of housing this bill specifically targets:

- In the 100 percent affordable housing developments built by Domus Development, the bill's sponsors, the average three-person family, usually a single mom with two kids, earns about $24,000 a year

- Twenty percent of California's seniors live below the poverty line

- The poverty line ranges from around $11,000 a year to $16,500 a year, depending on location and how it is calculated

- The average annual cost of owning a car is $8,876 a year

- Average construction cost of a parking space in the US is $24,000 for an above-ground space and $34,000 for a below-ground space [PDF]

- TransForm's GreenTrip program found that 31 percent of parking spaces at affordable housing developments in the Bay Area—not just in San Francisco--are unused.

Affordable housing developers rely on funding from programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax credit, which gives private investors an incentive to put money into housing in return for tax credits. Those tax credits help fund the parking that is required by local jurisdictions, whether it is used or not. So, instead of buying affordable housing, government funds are paying for parking to satisfy local requirements.

The bill still has active opposition from the League of California Cities. Its website features a tone-deaf form letter that claims that the bill "effectively eliminates local parking requirements" (if only it were so!) and that it's unfair to take parking spaces away from seniors, low-income, and special-needs people.

But the bill has a long list of supporters, including housing advocates throughout the state, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the California State Treasurer, and a number of cities. The California chapter of the American Planning Association, originally opposed to the bill, has taken a “support if amended” position, looking for clarification about what a parking study would entail.

The members of the Governance and Finance committee that will hear the bill next are:

Senator Robert M. Hertzberg (Chair) (D-Van Nuys)

Senator Janet Nguyen (Vice Chair) (R-Garden Grove)

Senator Jim Beall (D-Santa Clara); Beall is chair of the Senate Transportation and Housing Committee and supports the bill

Senator Ed Hernandez (D-West Covina)

Senator Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens)

Senator John M. W. Moorlach (R-Costa Mesa)

Senator Fran Pavley (D-Agoura Hills)