This week, Streetsblog California takes a look at changes occurring in Oakland, California, related to the way the city plans and implements transportation projects.

Today, Ruth Miller, a local planner, former Streetsblog contributor, and a member of Transport Oakland, writes about what the formation of a Department of Transportation will mean for Oakland. Later this week look for Streetsblog's interview with Matt Nichols, the city's newly hired Director of Transportation Policy.

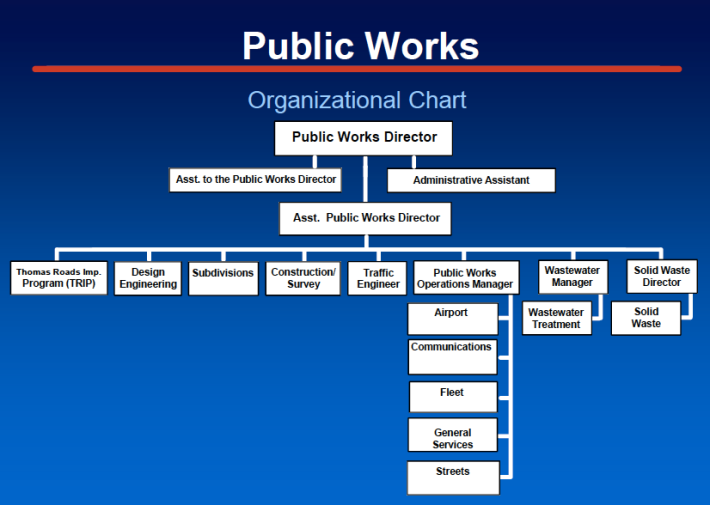

Like a surprising number of other cities, despite its size, Oakland, California, currently does not have a Department of Transportation. Decisions about transportation projects from signal timing, to paving, to designing and applying for grants to fund a bike and pedestrian bridge over the estuary leading to Lake Merritt, have been made within either the Planning Department or the Department of Public Works―or both.

But if Oakland's new mayor, Libby Schaaf, has her way, this will change soon. Her proposed 2015-17 budget, currently under discussion, includes within it a reorganization of city departments to create one specifically for overseeing transportation policy and decisions—a Department of Transportation (DOT). Advocates for better transportation choices in Oakland, including the advocacy group Transport Oakland, believe that creating a DOT could help the city better plan for and manage its transportation.

DOTs often publish mission statements.

For example, the Los Angeles DOT “leads transportation planning, design, construction, maintenance, and operations in the City of Los Angeles.” The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, which is equivalent to a DOT, works “to plan, build, operate, regulate, and maintain the transportation network.” [PDF] Essentially, these, and most other city DOTs, lead transportation projects from policy through planning, implementation, and maintenance. Because they govern the full life cycle of transportation projects, DOTs have the ability, and thus a certain obligation, to work strategically.

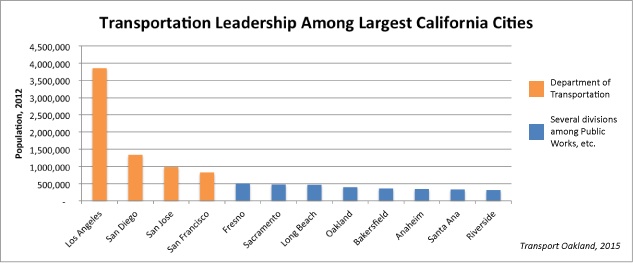

In a city without a single transportation-focused department, these responsibilities get carved up and scattered across other corners of government. In Oakland that's meant transportation planning and projects are mostly split between the Planning Department and the Department of Public Works. Other cities in California divide their transportation work in other ways:

- Sacramento has separate divisions for Transportation and Parking Services within its Public Works Department.

- In Fresno, transportation is split into several divisions within Public Works: Streets, Traffic Engineering, Capital Management, and Facilities Management. Parking is in a separate department entirely: the Development and Resource Management Department.

- Bakersfield’s Operations Department has a Streets Division, while three separate divisions for Traffic, Capital Improvements, and Subdivisions reside in the Engineering Department.

With these sorts of fragmented hierarchies, many transportation staff end up reporting to people without any specific transportation experience. Consider the significance of how a city regards parking. It can be seen as a resource akin to open space, to be divided up according to demand. Or it can be seen as a consequence and cause of the choices people make in how they travel, and it can be managed in a way that can encourage or discourage trips by various modes. In a city where parking management and transportation planning happen in different departments, the division between these two perspectives can deepen.

For these reasons and more, cities without DOTs often end up focused on maintaining outdated transportation policies, and can find it difficult to coordinate strategic planning or an overarching vision for what transportation could be.

Most crucially, cities with DOTs win more federal grants, deliver more projects, and earn more recognition from other cities and planning organizations. “Cities with DOTs produce quality projects that get recognized more often,” reports Karl Anderson, a graduate student at UC Berkeley. “Twice as many FHWA and FTA awards have gone to cities with DOTs [as those without one]. Additionally, more than half the American Planning Association awards from the last fifteen years have gone to cities with DOTs.”

These figures are even more striking given how few cities have DOTs. Only eighteen of the fifty largest cities in the United States, including four of California’s twelve largest cities, have transportation departments. Oakland is the eighth largest city in California in terms of population.

Among smaller cities (those with under half a million residents), DOTs are substantially less common.

Anderson and others compiled this research as volunteers for Transport Oakland, a group of transportation advocates that want to improve Oakland's transportation choices and that have advocated for Schaaf’s DOT proposal. Transport Oakland estimates that the City of Oakland missed out on over $15 million in street paving funding in 2013, merely because the city lacks staff dedicated to developing and managing a project pipeline. Considering that Oakland is on an 85-year paving cycle, where thirty years is the average, these funds are sorely missed.

Mayor Schaaf will lead a series of Community Budget Forums through June 30, when the City Council is set to adopt a final budget. If a DOT is included in that final budget, hiring and realignment can commence this year. Supporters are quick to point out that the DOT proposal is budget neutral for the city, which will benefit from a cash infusion from the recently passed sales tax Measure BB, and because although new staff will be hired, the proposal mostly relies on a strategic realignment of existing staff. Transport Oakland says that enabling the City of Oakland to strategically pursue a pipeline of innovative projects and external funding could even pay for itself in the near future, by helping secure future funding for good projects.

"Right now is a very special time for Oakland,” says Transport Oakland co-founder Liz Brisson. “We have money, we have political leadership, and we have strong public support for sustainable transportation.”

Schaaf has already used Measure BB funds to create the new position of Transportation Policy Director for Oakland, for which she hired Matt Nichols, a former senior transportation planner from the City of Berkeley.

With new transportation funds and a new transportation-supportive mayor, 2015 was already off to a promising start in Oakland. Now supporters are hopeful that a new DOT will deliver the kind of innovative and strategic transportation planning for which the city has long hoped.

Check back later in the week for Streetsblog's interview with Matt Nichols and more on what this change means for Oakland.