Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Building an integrated transit network, where customers are no longer confronted by a frustrating mess of uncoordinated fares and schedules, “can actually be a lot of fun,” said Thomas Straatemeier of Goudappel, a Dutch transportation consultancy, during a SPUR panel discussion Wednesday afternoon.

Key to developing a user-friendly, integrated system is remembering it’s about the experience of the customer, not just moving buses and trains. “Thirty to forty percent of the overall travel time is actually within the transit vehicle of an average trip. Sixty to seventy percent is spent going to and from the transit stop, [and] waiting to change at the station,” said Straatemeier. “If you’re talking about a connected network plan, you talk about more than transit service.”

That means considering the availability of bike share and other ways of solving first-and-last-mile problems. It means frequent, clock-face service, all day long. And it means transit stations are pleasant, inviting places that people want to spend time in.

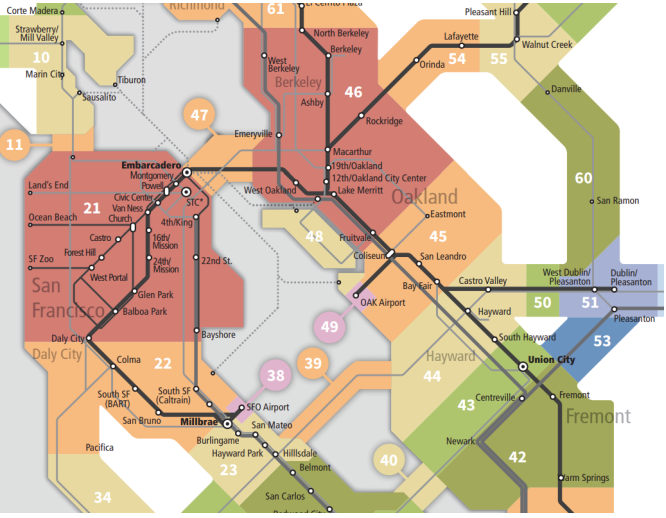

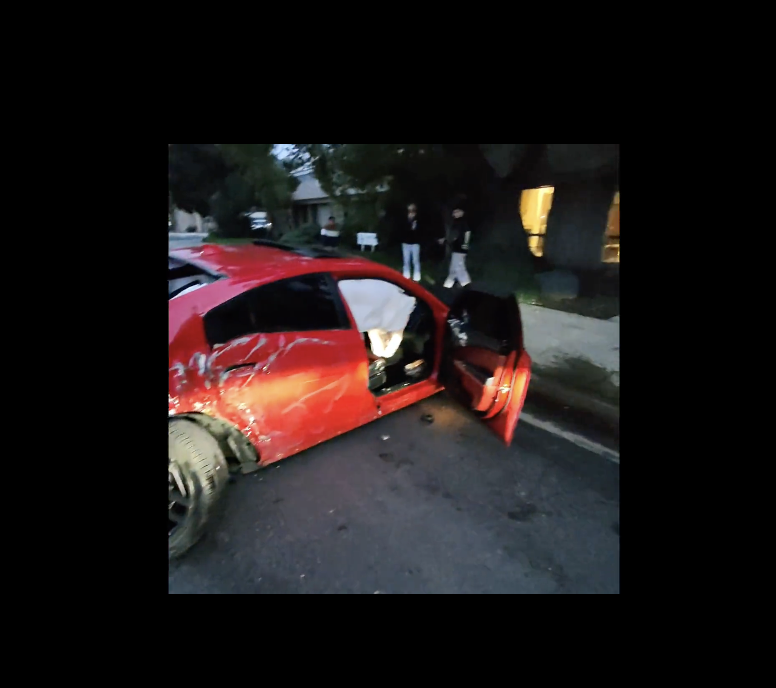

In other words, not the Bay Area–not with its 27 operators, each with its own fare system, branding, schedules, sub-par stations, and this:

Those are the iron jail bars that divide BART from Muni in downtown San Francisco. To change between the two systems, instead of crossing the platform blocked by these bars, one must climb a flight of stairs, go through an exit gate, cross a mezzanine, go through another set of fare gates, pay another fare (no transfers allowed), and go down another set of stairs only to, more often than not, miss one’s connecting train.

The SPUR panel discussion underscored how these ridiculous, ongoing conditions are a reflection of the people who manage and operate the systems and the government agencies that oversee them. “When you have funding that’s siloed between regional and local, and authorities that are distributed, it makes finding that shared space of accountability really tough,” said MTC head Therese McMillan, another of the speakers. “It’s a structural pattern that’s been around so long… local isn’t bad. Regional isn’t bad, but we’ve made them competing against each other instead of complementing.”

In fact, McMillan spent much of the time talking about bureaucracy and studies and warning people not to get dreamy about integrated maps, like the lead image and the one above. She also talked about the many studies conducted by MTC, including the Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task force, which met for over a year, and which she says may be finally moving the agency towards a “re-imagined future grounded in a customer, consumer perspective.”

If there had been time for questions, one could have asked why it took fifty years for MTC, which was created to integrate Bay Area transit, to decide the customer should come first.

Meanwhile, Lisa Salsberg of Access Planning in Ontario, Canada (another region with integrated transit) explained how the world has changed since the days when most people commuted back and forth from suburbs. “1970’s planning for that regional transit network was not as complicated—people went from the suburbs to downtown. Today the trips are going all over the place.”

That was why Ontario worked to integrate its system, a necessary step to allow transit to work for more complicated trips. Ontario Metrolinx, that region’s network manager, was created in 2006 “…to improve the coordination and integration of all modes of transportation in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area.” Metrolinx is still working at it, but it has accomplished more in sixteen years than MTC has achieved in over fifty. To McMillan, however, who started at MTC in 1984, there was no need to integrate transit until “COVID changed everything.”

Of course COVID put financial pressure on transit systems all over the world–including in the Netherlands and Ontario. But putting up bars–both literal and metaphorical–between the transit systems of the Bay Area was always a bad thing. They are an in-your-face metaphor for the failings of Bay Area governance and leaders.

One takeaway from Wednesday’s discussion is that the people who perpetuated the Bay Area’s fragmented system for so long are not the right ones to fix it – nor to convince operators to stop “looking in the rear-view mirror at February 2020 and start looking [out] the front windshield,” to borrow McMillan’s unfortunate, car-bound metaphor. It’s clear the Bay Area is never going to integrate its transit until it replaces that old guard with realistic but positive people who actually value making a system that works.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.