Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

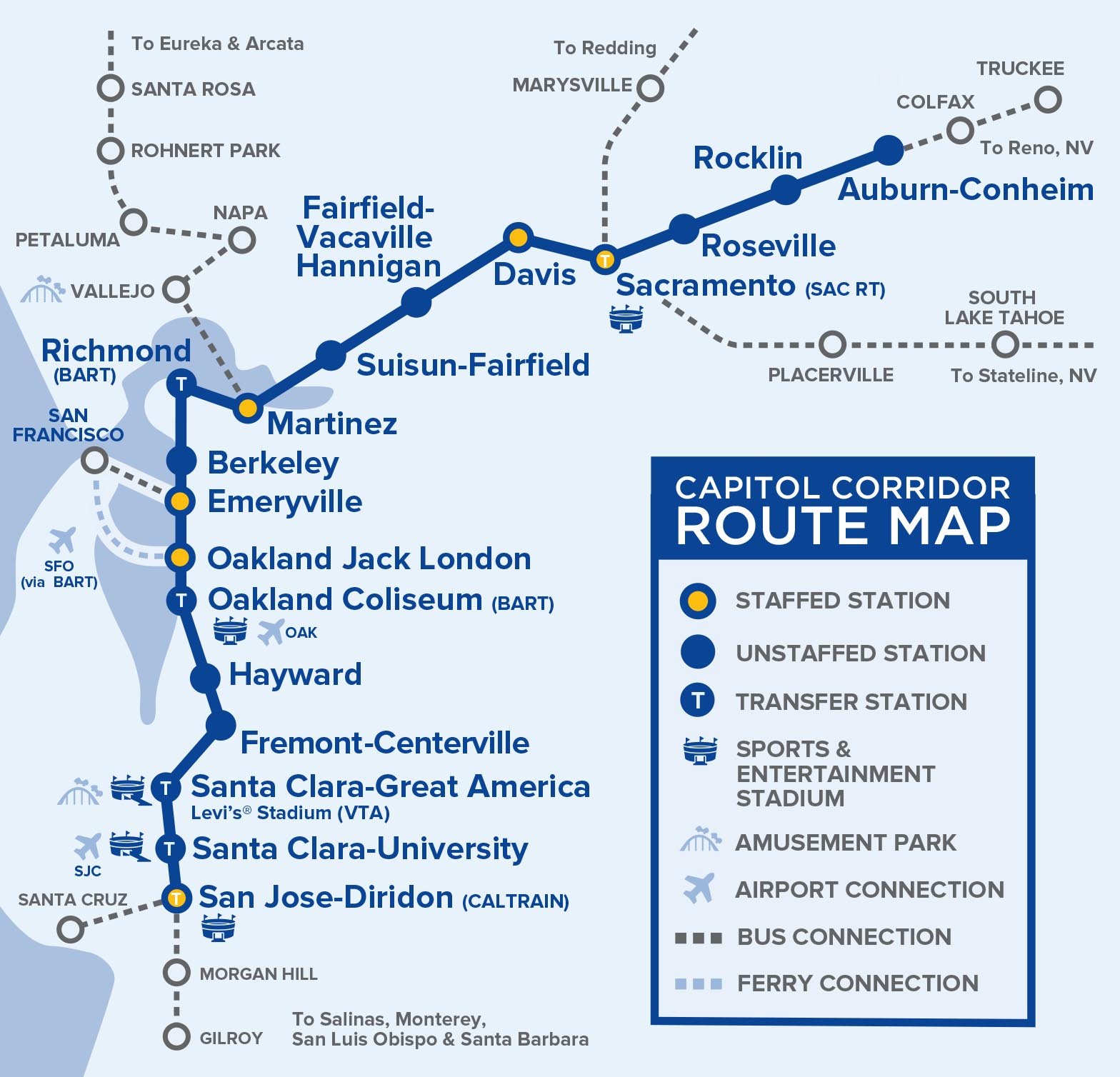

Anyone who rides Amtrak's state-sponsored Capitol Corridor trains between Sacramento, the Bay Area and San Jose knows they are often significantly delayed. But unless they ride north of Martinez they may not know why--it comes down to a 90-year-old draw bridge that requires trains to stop for ships passing through the Carquinez Strait.

"Those of you who have ridden the train frequently have probably been stopped at the bridge," explained the Capitol Corridor's Planning Manager, Jim Allison, during the service's regular Board Meeting Wednesday morning. "It can take twenty minutes."

Up until now, said Allison, the focus has been to work with the Coast Guard and marine freight operators to schedule shipping around train crossing times to minimize delays. However, it's become clear that the dream of European-style, reliable, half-hourly regional rail service will be impossible with this current arrangement. Plans are in the works for additional passing tracks, realigning of parts of rights of way, signal improvements, and additional trains up and down the corridor, but "...all the millions we might spend will be for naught unless we replace this bridge."

The new bridge will have to be about 160 feet feet from the surface of the water, so shipping traffic will be able to get underneath without requiring a movable section that forces trains to stop and wait.

Allison said there's some $1 million available in current budgets to start studying the best place to build a new "high bridge crossing" and how to get the work done. Additional funding for engineering work, upwards of $5 million, is also possible--and obviously it will take far more to actually construct it.

The high bridge study will explore building the crossing either near the current location or farther west, closer to where Interstate 80 crosses the straights. Either way, the biggest challenge is not the bridge itself but the approaches, since trains will have quite a climb, requiring miles of new tracks. One of the biggest questions is whether to build the bridge to also accommodate freight trains, which, depending on the ratio of locomotives to freight cars, can handle a .5 to 2 percent grade. Passenger trains can handle climbs twice as steep, so costs should be much lower if the new bridge is passenger-only and freight trains continued to use the existing bridge.

Robert Padgette, Managing Director for the Capitol Corridor, said the Biden Administration's focus on rail as well as new state funds for intercity rail projects means it's an opportune time to study these options and get the project ready. "The signal is there that intercity rail will be an important part of our federal transportation bill.”

From Streetsblog's view, there's perhaps no situation that better illustrates the country and state's fixation over the past half-century with infrastructure for automobiles and trucks. There are four super-wide highway bridges across the straight, with 20 lanes in total, all built at taxpayer expense and high enough for ships to pass underneath. But there's only one rail bridge, the width of two traffic lanes, across which all freight and passenger rail is supposed to cross. It's nearly a century old and was built by a private company--and is still owned by a private rail operator.

How are trains supposed to compete with cars and trucks under such circumstances?

If the state is serious about reducing emissions from automobiles and giving people alternatives to traffic, it's imperative to build rail crossings that are reliable and aren't cut off every time a ship goes by. That's also means rebuilding the Dumbarton Bridge project farther south and the proposed second-Transbay crossing between Oakland and San Francisco, so the rail systems reaches at least as far and wide as California's freeways.