The Canadian Urban Institute recently held an online panel centered around the question of “How do we respond to anti-Black racism in urbanist practices and conversations?” The participants in the all-Black panel were Orlando Bailey of Detroit (BridgeDetroit and The Urban Consulate), Tamika Butler in Los Angeles (Toole Design), Will Prosper in Montreal (Montreal-Nord Republik), and Anthonia Ogudele of Vancouver, BC (Ethos Lab). Jay Pitter, a fellow of the CUI, moderated the discussion.

The first question to the panelists was, “What was your first experience of alienation or threat within the public realm?” Anthonia recalled being teased about her Black skin on the playground as a child. “It’s interesting that playgrounds are seen as a source of joy in the city,” she said, and yet for her they were not. Orlando recalled that when he was a child visiting a Saks Fifth Avenue with his aunt, an employee asked her to leave him and other young family members outside.

Tamika, a leading Black voice in bike advocacy and urban planning, shared that when she asked her parents about incidents of racism that occurred when she was a child, at first her parents didn’t remember them. As the conversation went on, however, they started to remember the events. Tamika said many Black people suppress memories of racist incidents in order to survive. She recalled that school for her was a place where “folks wanted me to know who I was and what my place was.”

Jay then asked the panelists how they are managing the dual crisis of a disproportionate number of COVID-19 cases within the Black community, and high-profile cases of Black deaths at the hands of the police. Orlando, who works as a journalist in Detroit, a city that’s 79 percent and has had a high COVID-19 fatality rate, said he had to step away from the work at one point. He also contracted the virus and has lost close friends to the disease. He interviewed the chief officer of corrections for the state of Michigan, who assured him that the prisons were safe and that if an outbreak of COVID-19 occurred, it would be handled appropriately.

Orlando has two family members who are incarcerated in Michigan. One of his relatives told him about the conditions within the prison that make social distancing impossible. Orlando used his platform to call attention to the conditions and demand change. He noted that one of his family member stated, “I was not sentenced to die.”

Tamika said that quote resonated with her. She revealed that many times she has thought, “Because I’m Black, I’ve been sentenced to death prematurely. I’ve been sentenced to death based on things that people in power who are white are going to want me to believe are based on choices that I’ve made. In reality, they have done everything to make sure that the options of Black folks are limited because they don’t want to cede power or admit that they contribute to structures of White supremacy that they keep in place.”

I appreciated Tamika’s candidness throughout the panel. She spoke about the inability to focus on a “deliverable” to speak to “the moment” we’re in, for example, writing an article about urbanism and race. Butler said that lots of people are seeking out Black perspectives on “this moment” in the wake of the George Floyd protests. “Ooh, Black person! I’ll listen now!” To her this phenomenon feels like a “taking,” but she said she felt a huge pressure to say yes to recent interview requests for fear of not being sought out after this moment.

Recently I’ve been pondering how long the current interest in hearing from Black voices will last. Will the present mainstream focus on our experiences and needs extend beyond this current moment, and will it lead to lasting change? Will Black people be seen as more than just experts on Blackness? I’m not sure.

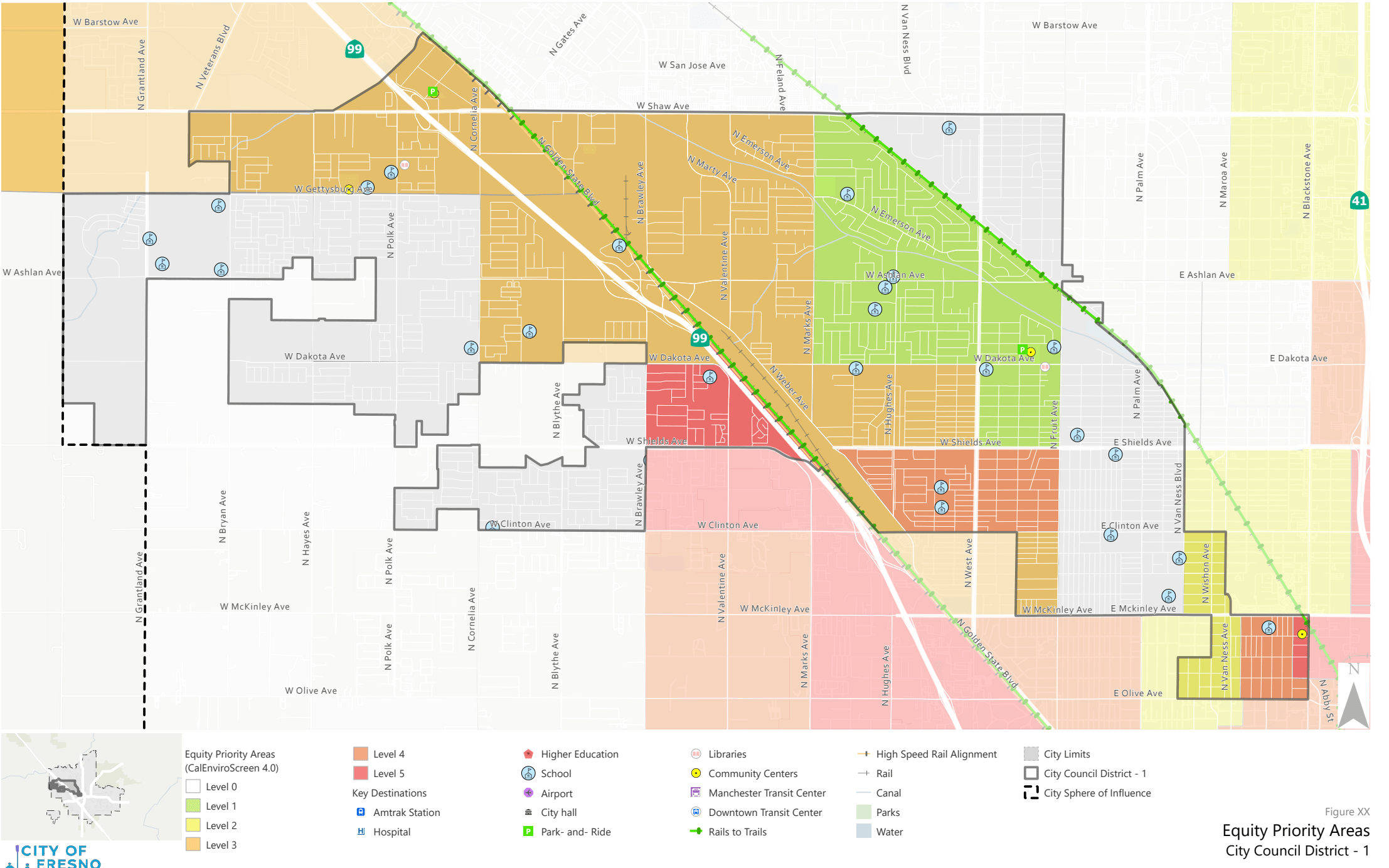

My hope is that the current conversations within the urbanist field and at the Chicago Department of Transportation will lead people to value the voices and genius of Black people. Black Chicagoans on the South and West sides know what their communities need. It is time we see them as the experts on what would benefit their neighborhoods and not impediments to what our vision of progress looks like.

During the panel, Jay asked, “What is the one way urbanism or city building has failed Black people?” I was struck by Orlando’s response that “authentic co-creation and civic engagement is seen as a chore and not a privilege.” When city planners view the need to focus on equity and community engagement as a burden or speed bump, the seeds of mistrust between planners and the African-American and Latinx communities they are tasked to work with have already been sown.

This issue highlights the need for more Black and Brown planners. It also calls for expanding the definition of who is an expert on city building to uncouple that expertise from post-secondary training. It also calls for planners who aren’t Black or Latinx to really engage with the work of those who are, and equitable frameworks for city building.

When I recently interviewed Warren Logan, policy director of mobility and interagency relations for the mayor’s office of Oakland, he said officials in that city view communities as partners in the effort to improve the city, and experts on their own needs. Orlando’s comment underscored why that approach is so important.

Tamika added that one of the failures of urbanism has been the inability to listen to and believe Black people, and the notion that Black people owe white people something. If non-Black planners truly engage with the experiences of Black people within the public space, they can help make those spaces safer. Livable streets advocates emphasize the need to make streets safer for children and elderly folks. It’s time to broaden the definition of livable streets to include public space where all people are free from the threat of violence by police or racists, as well as interpersonal violence.

Anthonia echoed Tamika’s sentiments and added that when she brings up equity, she’s brushed off. “Everyone at the table needs a competency and understanding of our shared humanity. We are not challenging the transportation engineers; we’re not challenging the professionals around the table.” Just as racism is embedded in numerous facets of our society and the systems that make up our society, the work to undo racism must be embedded in every process and system that impacts access to public space.

If you’re interested in hearing the talk in its entirety, the Canadian Urban Institute will be sharing the recording on their website in their CityTalk section.