Americans who are wondering how they can help reduce the looming impact of COVID-19 can start with the easiest of actions: driving slower.

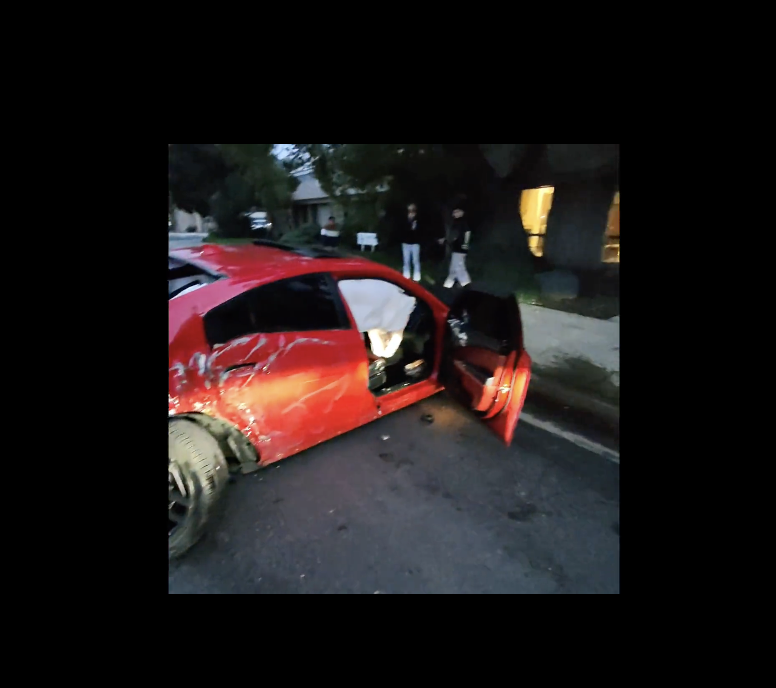

The crisis will soon push America's hospitals past the breaking point — but as medical professionals prepare for that crisis, cities, states and the federal government can help them by taking immediate action to reduce hospitalizations from the most preventable cause: car crashes.

Traffic violence puts pressure on the health care system even in the best of times. Car crashes are consistently among the leading injury-related reasons for emergency room admissions in America; when you include cyclists, pedestrians and other vulnerable road users in motor vehicle crash totals, as many as 5,170,000 traffic victims visited U.S. hospitals in 2017, 40,100 of whom ultimately died, according to the CDC.

Even survivors need more of our healthcare system's scarce resources than people with other injuries — resources we can't spare as the coronavirus spreads. A staggering 70.2 percent of traffic violence victims need medical imaging services, for instance, compared with just 55.9 percent of patients suffering from other injuries. That means car crash victims could capitalize much-needed CT scanners and X-ray machines as our population gets sicker from COVID-19.

People with traffic injuries are also more likely to arrive to the hospital by ambulance — they do so 42.9 percent of the time, compared to 16.6 percent for other injuries — which compromises crucial emergency response times and makes it more challenging for COVID-19 patients to make it to the hospital without exposing others.

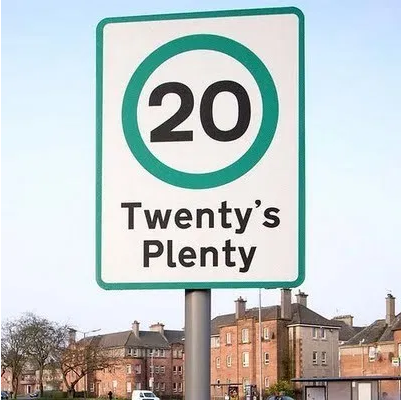

There is some evidence from Los Angeles and Seattle that fewer people are on the road right now. But communities that want to make their streets even safer can do one simple thing:

Reduced speed limits are the chapter and verse of the safe streets gospel for a reason: the slower the car, the less chance it will cause injury and hospitalization. Proof? Helsinki and Oslo both virtually eliminated traffic deaths in 2019, in part, by lowering speed limits in most urban areas to under 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) per hour.

As much as possible, cities would be wise to reinforce these new speed limits with road design to support those who are forced to travel outside their homes — and in an emergency situation like this, that means it's time for quick-build tactical urbanism projects that don't require street crews to spend too much time outside of self-isolation. At the very least, simple traffic-calming measures and temporary walking infrastructure should be a part of every city's early emergency response plan from here on out — and we should reallocate road space to make those pop-up sidewalks deep enough that walkers in dense areas can maintain the CDC-recommended six feet of distance between one another.

(Even better: let's just make those deep sidewalks permanent. Because they'd save lives, whether or not another pandemic ever happens.)

But no matter what we do on our streets, epidemiologists believe our focus for now should be on staying indoors as much as possible — and making plans for a less car-dependent future.

"I hope this is making us question all the ways that our systems are failing right now, and that includes healthcare and also our infrastructure network," said Eva Siegel, a doctoral candidate in epidemiology at Columbia University.

Making plans to make our communities less car dependent sounds like a great way to while away the hours in self-isolation to us.